Nowhere does Australia’s melting pot multicultural society play out more obviously than through food. It tracks our history of immigration, our sometimes troubled journey to social integration and acceptance, and our recalibration as a nation of many finding common ground in a diverse national identity.

When he was seven years old, my father came to Australia by boat from Sicily. Along with his mother and sister, they joined his father who was already here, building railways and cutting cane. They had no English and no context for the Antipodean metropolis of 1950s Sydney. They came from a tiny island in a Mediterranean archipelago where donkeys were the usual mode of transport and those who left were farewelled by wailing widows insisting they’d meet their end at sea.

My grandparents only ever returned in their minds. My nonno would sing out of tune, tears pooling in his blue eyes, as he gazed at a picture of Lipari’s Marina Lunga on the kitchen wall. Sipping the vino he fermented in his Ashfield garage and drumming his fingers on the Formica tabletop, he’d tell us in his lilting English of the home he once loved.

My father took us home to Lipari when we were old enough to pay attention. We recognised our own features in the faces of our lost relatives and, with language virtually useless, we spoke through food. We revelled in the regionally specific treats we all knew, even though we now came from opposite sides of the world. Throughout the decades between, the Australian diaspora of the Picone clan had diligently kept the flavours of the ancestors alive and there they were, served alongside a limoncello at 10am.

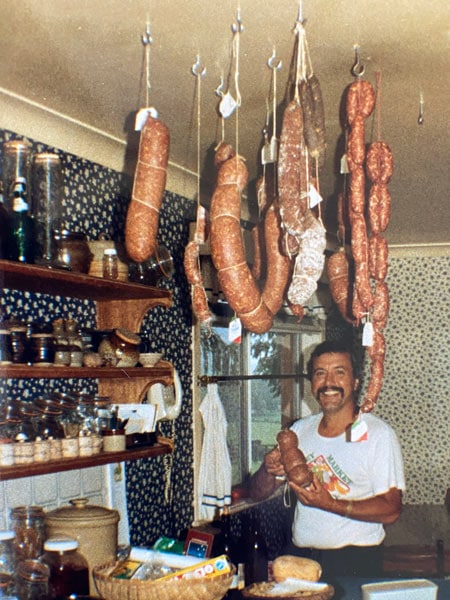

Food has always been the language of my family. Despite copping near-daily beatings for being a ‘wog’ as a kid, my father never lost his passion for the flavours of his homeland. A masterful cook, he spent years resurrecting recipes from the taste memories of his childhood and sharing those with family and friends.

By the time I was at school, Australia was a different place. And although my friends would recoil in visible distaste at the sight of the absurdly bulging cacciatore, petrified fish, and homegrown garlic plaits hanging from our kitchen ceiling, I felt a small but meaningful surge of pride.

By high school, my brutish sandwiches stuffed with hunks of parmesan, slabs of salami and glistening with olive oil were the hot ticket for lunchtime trades. They’d fetch the high price of an Uncle Tobys choc-chip muesli bar and a packet of Chicken Crimpy.

My own exposure to ‘other’ food ignited an adventurous palate and a love for all cuisines that not only spurred my hunger for travel but also shaped my career. But I am far from alone; many Australians have a similar back story.

The history that underpins what we eat

Of course, apart from our First Nations people, we’re all from somewhere else. This ‘elsewhere’ has coloured the rich and diverse food culture we hungrily devour in Australia today. It’s how we can walk down many suburban high streets and have our olfactory senses infiltrated with the tempting aromas of everything from pizza to roti to lacquered-red barbecued duck.

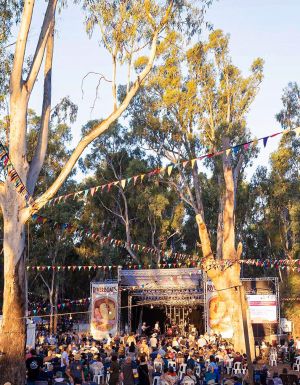

Beginning with the Chinese gold miners who set up eateries wherever they went, to the arrival of Afghan cameleers and Japanese divers in the latter 19th century, onto the influx of Italian and Greek migrants following the Second World War, followed by the arrival of Southeast Asian students in the ’90s, and asylum seekers arriving from the Middle East and Sri Lanka, each wave of migration has essentially brought a plate to the party, which we’ve happily added to the national menu.

It didn’t happen overnight or without a good deal of initial scepticism (at best) and racism (at worst). But our meat-and-three-veg has evolved to incorporate myriad interpretations inspired by our wonderful migrant populations. Every newcomer has brought with them a pantry of thrilling new flavours, which eventually filter into our mealtime repertoires.

Ingredients such as garlic and coriander may be supermarket staples now, but when my father first arrived, you had to grow your own. Stroll the suburbs today and you can tell where an Italian lives by the requisite fig and lemon trees, trellised grape vine and prickly pears planted between the watered concrete slabs.

Celebrated chef and cookbook author, Christine Manfield recalls a time when the sight of an avocado was astonishing. “I remember my excitement as a young adult in the ’60s when the first pizza place opened in Brisbane, and seeing basil for the first time and avocados, all these things that were foreign."

Similarly, Chat Thai restaurateur, TV presenter and organic farmer, Palisa Anderson of Boon Luck Farm in northern NSW, recalls the difficulty her mother, Amy Chanta, had in procuring ingredients for her Thai restaurants as recently as the ’90s. “Even then she had to adapt her recipes because there were not a lot of ingredients being exported from Thailand," says Anderson. “Coriander was not easy to get. And I had to separate the cream out of the coconut milk cans. Ingredients were hard to find up until the 2000s."

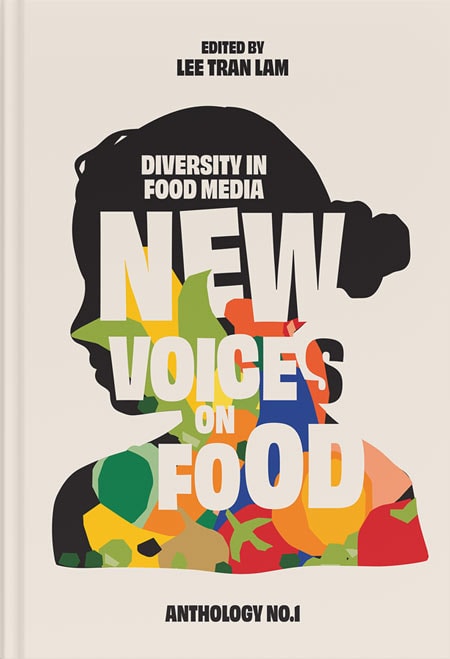

It’s difficult to imagine an Australian pantry without soy sauce or a boozy night ending without a kebab. Yet even as some pockets of the country teem with vast food offerings, it can be a slow trickle down to the most resistant palates. Still, our interwoven food culture is evident in the most Aussie of institutions, the pub menu. Grab a counter meal around the country and you’re likely to find subtle hints at our migrant heritage: in salt-and-pepper squid, a Thai beef salad, or laksa. “Even though they might be really bastardised or watered-down versions, there’s still a slight reflection of things beyond just steak and chips," says Lee Tran Lam, editor of New Voices on Food.

“What’s interesting is when you don’t have to explain things anymore. If you don’t have to explain what banh mi is anymore, it means that’s mainstream," says Lam. While she agrees Australia’s food culture is rich, there’s a lot more we could be seeing when it comes to variety on the plate, on our screens, and how we value food. There’s also changes we need to make to ensure the way we eat is inclusive, sustainable and fair to those who make and produce it.

Today’s food landscape

However willing we may be to embrace the flavours of the world, we shouldn’t pretend it’s a rosy pot-luck picnic of equality. Even if we open our stomachs to different cultures, other facets of Australian life can be at odds with our shared table.

“Food, like nothing else, can connect the most unlikely of bedfellows. And, in Australia, food is what brings many of us together. But all you need to do is take a deep breath and look at how politics and perceptions play out in this country to see that we are still shuffling the deck when it comes to the acceptance of migrants and the different aspects of different cultures," says Anthony Huckstep, restaurant critic and host and co-founder of food, drink and travel podcast network, Deep in the Weeds.

While it’s often through food that acceptance flourishes, it can also highlight underlying biases or at least blind spots in our tolerance. Lam echoes this sentiment using Prime Minister Scott Morrison as an example. Whatever your opinion of his leadership, his tone-deaf Instagram posts about making a curry, while simultaneously refusing entry to the country from India when COVID-19 cases surged there, feels uncomfortable. In light of the government not enacting the same policy for the United States or Italy, it’s hard not to see a racial link. “Someone can make a curry and still have bigoted perspectives, unfortunately," she says.

Embracing cultural ‘otherness’ is a process of evolution. Take my salami sandwich, for instance. Had my father produced that in the playground of his era, he could’ve expected a swift left hook and derogatory insult, whereas I expected a bidding war. Eventually, as fear of those 1950s newcomers dissipated and Australians found a taste for espresso and cannoli, Italian food became something to go out for. Along with other continental cuisines, pasta wound up at the height of sophistication.

“We’re from all over the place and that is celebrated through our food. It’s certainly not celebrated through our political or social systems. That’s where food is great. That’s where it can be such a great salve," says Manfield. While we may initially feel confronted by the customs of another culture, we can all agree that Indian jalebi is delicious and we’ll happily share a plate of shawarma with our Middle Eastern neighbours. From there, doors open to respecting and eventually revelling in difference.

The problem with ‘cheap and cheerful’

Yet that difference still falls into a hierarchy, depending on just how different it is. Since we began eating out in Australia, fine dining establishments have long been the domain of white chefs cooking European food. It’s only been in the last decade or so that we have come to view Asian, Indian and Middle Eastern food as anything more than cheap and cheerful. “That’s limiting because it basically says if it’s a non-white cuisine, it is only valued because it’s cheap. And that’s really unfortunate," says Lam.

Huckstep agrees, “Our society has learnt that the double white tablecloth, European-style fine dining is the pinnacle, which belittles the spectacular culinary offerings of so many cultures and cuisines. How can you compare the colour, vibrancy and energy of Thai cuisine with the rich, technical precision of French cookery? And why do we need to?"

We don’t. Our journey now as a ravenous, multicultural country is to abandon any ingrained notions of value associated with the origin of cuisines and, instead, evaluate the beauty of a restaurant based on the quality and sustainability of the produce, whether the staff and growers are paid fairly, and, of course, how delicious the food is. “It’s been that notion of, ‘Oh, it’s cheap to travel there, therefore everything there should be cheap’," says Manfield of the misguided siloing of Asian food as ‘cheap eats’. “It doesn’t translate back here where your wages are different, you’re paying for ingredients. So, quite wrongly, there’s been that distinction."

As both a farmer and restaurateur, Palisa Anderson is acutely aware of the cost of producing food and sourcing ingredients. She says we are incredibly fortunate to be in a country where we can grow just about anything, and yet there are much fewer farms these days. “A lot of food is imported and I think people need to stop expecting things to look a certain way. People who live in cities, through many generations, have forgotten what food is supposed to taste like," she says.

She’d like to see consumers thinking about where their food has come from and how it has impacted the person who made it. Through this you’ll be more understanding of the true cost and be happy to pay a fair price. “A good gateway to doing that is try your hand at growing some of the food you consume yourself. You’ll know and appreciate how much harder it is to actually bring that food to your plate," says Anderson.

Happily, things have been changing thanks to a new generation of chefs questioning old assumptions. Lam cites renowned American chef David Chang of Momofuku who asked why people are happy to pay exorbitant prices for pasta, but not noodles, which are often laboriously hand-stretched. His first noodle bar, which he opened in 2004, was ground-breaking and had a knock-on effect across the world.

“A lot of young chefs thought, ‘Oh my God, this guy opened up a ramen joint and that can be a good restaurant. It doesn’t have to have white tablecloths, it can be small, it can have really loud music’," says Lam, explaining that this played out in Australia, too, where our own Dan Hong, executive chef of Merivale, opened Sydney’s hip and hyped Ms.G’s. “The idea of what good food could be was made a bit more democratic," she says of Hong and his contemporaries.

Food and its power to influence political change

That democracy has flourished and although we’re still not out of the woods regarding some of our more ingrained biases, we’re catching on a lot quicker. Positive growth is also visible in the celebration of our Indigenous food culture, which was barely acknowledged until the 1980s and is just beginning to flourish in the hands of Traditional Owners and respectful chefs who pay homage to these ancient traditions. “Chefs are now taking the time to understand native ingredients, but we are only at the beginning of acceptance of the beautiful properties of Indigenous food and native ingredients," says Huckstep. “As a society, we are a long way from accepting our First Nations people as just that. But like migration, food is a little ahead of the social and political."

While we embark on an education of the endemic food culture and those that have since arrived, we also set out to explore other shores. Our love for travel means we will seek out flavours across the globe, returning home with greater appreciation for those who create them. “You can often overcome social obstacles by sharing the table with people you don’t know from somewhere else. And that also comes through travel. Travel and food have always been the symbiotic relationship," says Manfield.

“You don’t have to be Indigenous to cook Indigenous food. And you don’t have to be Thai to cook Thai food, but it’s about giving a recognition to and also submerging yourself in a deeper appreciation and understanding of that food culture," she says. “… it’s a recognition of equality and inclusion and food is a great place to start for that sort of political change, because you can do it really subtly and subversively."

Australia’s appetite for cultural diversity

Ultimately, our national appetite is swelling to reflect a celebration of diversity. It’s richly flavoured with the cultures of those who were here first and those who have made Australia their home. We’re an open, intrepid bunch and we live in a country of abundance, which means we possess the great ability to be welcoming to others.

“In Australia, we have such great produce, and an amazing pool of talent in terms of restaurateurs, chefs, entrepreneurs and the migrants who come in and cook their food," says Anderson. “There’s no shortage of plenty. So when you’re not hungry, how can you be really upset?"