If necessity is the mother of invention, then the harsh Australian outback has provided the absolute mother of all incentives to find easier and better ways to do things over the decades. AT presents some of our most famous, and most astonishing, outback inventions and innovations.

Australian ingenuity has seen the invention of some world-altering technologies, gadgets and ideas – from simple yet revolutionary concepts like Hargrave’s box kite in 1893 to the famous Black Box flight recorder, brainchild of Melbourne’s Dr David Warren in 1956. But it’s the inventions born of the harsh and challenging conditions of surviving and thriving in the outback that are the most fascinating.

The Coolgardie Safe

Under the white-hot desert sun, it was damn near impossible to chill beer in the 1800s. All well and good if you’d just arrived from England and loved warm beer, but for the majority, this was unacceptable! Refrigeration technology was in its infancy, too cumbersome and far out of the reach of the average prospector’s pay packet. Sick of rapidly rotting food and warm beer, Arthur McCormick, a contractor in Coolgardie in WA’s eastern goldfields, rectified this problem with what became known as the Coolgardie Safe. Here’s how he did it: placing a wooden or steel frame in the shade where a breeze would regularly come through, a water tray then sat on top with Hessian sheets dipped in and draped over the sides. The water soaked in and dripped down. When a breeze hit, the water evaporated, drawing the heat out and leaving a cooler interior for the food (and beer). McCormick went on to become Mayor of Narrogin, but we firmly believe that, for his beer-cooling invention alone, he could have made it all the way to PM.

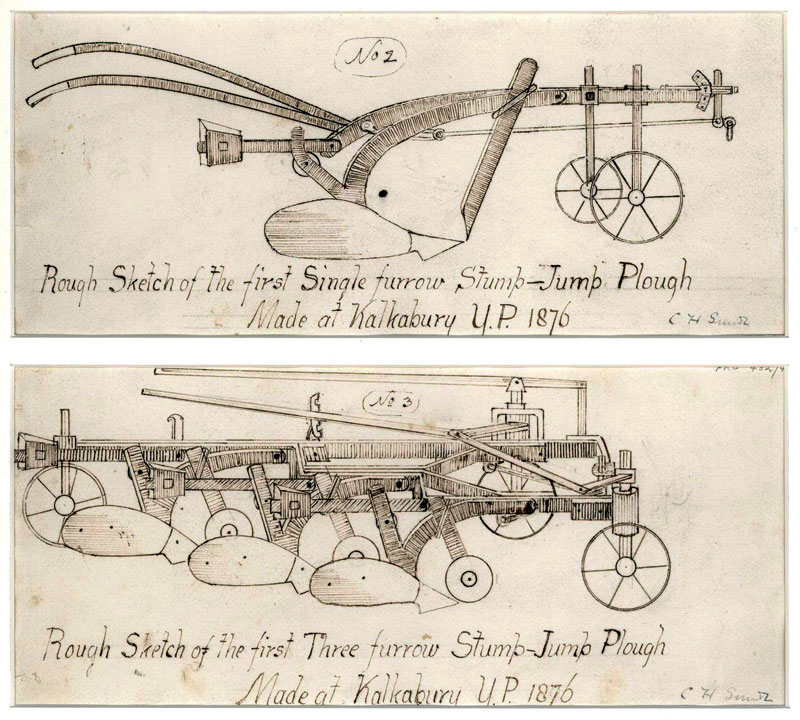

The Stump Jump Plough

The Mallee Bush is a stubborn character. So stubborn that in 1878 the SA government put a £200 bounty on its head for anyone who could come up with a technique to pull out the exasperating stumps. But the simple brilliance of inventor Richard Smith was to ignore the trivialities of stump removal altogether. He decided it was just as easy to find a way to jump over them than to waste energy pulling them up, by taking a regular fixed ploughshare and hinging and weighting it. The forward force of a dray dragging the blade would no longer stick it in the ground at every obstacle; instead the hinge would allow it to lift from the ground and fall back in when it cleared the other side. Though considered unconventional at the time, this basic design proved so cost-effective that it’s now used right across the agricultural world.

The Boomerang

The humble boomerang is thought to be the world’s first manmade, heavier-than-air controlled flying object. And while other cultures have developed similar sticks using an aerofoil uplift design, Aboriginals invented a boomerang that is unique in its ability to return to its thrower. This is because the boomerang relies not on a straight edge, but a curved one, allowing for an elliptical flight path. They’ve been variously used for hunting, hand-to-hand combat, musical instruments and cutting off fingers in Mel Gibson films. They’re even used the world over as a modern sports item these days. All this became possible without intimate knowledge of Newton’s Laws of Physics, the need for wind tunnels, taxpayer-funded laboratories or supercomputers. It was created out of nothing more than trial and error and the need to catch tonight’s dinner.

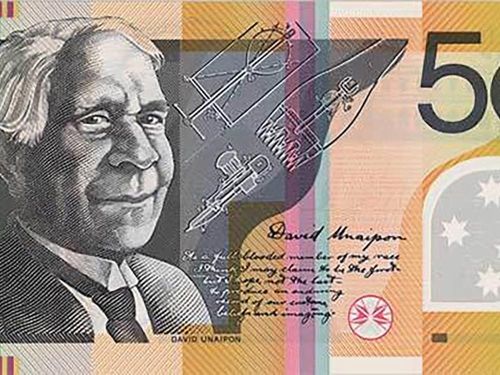

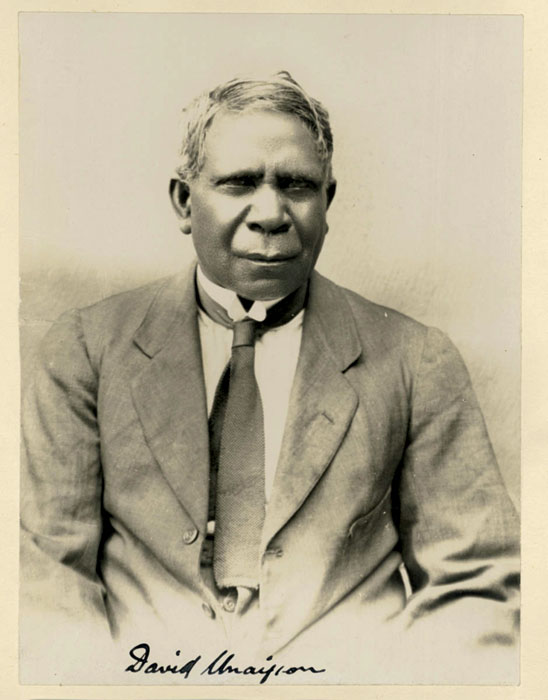

Genius inventor David Unaipon

It either takes a special kind of genius or a fool to chase the dream of perpetual motion. Ngarrindjeri inventor David Unaipon is saved from fool status by his lifetime of ingenuity and achievement against seemingly insurmountable obstacles. But that’s not to say he wasn’t treated the fool. He was. Not because of his pursuits – perpetual motion had its fans during Unaipon’s lifetime – no, David was treated the fool for being Aboriginal.

As a youth, Unaipon was busy filling his mind with science, literature and music, defying the racist beliefs that Aboriginals could barely participate in civilisation, let alone contribute in any meaningful manner. He applied for multiple patents on inventions he created – but was granted just ten. Among these were a centrifugal engine and multi-radial wheel. His most recognised was a then new mechanical handpiece for sheep shearing but, as an Aboriginal, he was unable to raise the cash to fund his own production. The design was pilfered and he never saw a cent from the subsequent explosion in demand.

Unaipon also saw the potential for a fixed-blade helicopter that utilised the aerofoil design of the boomerang, overturning the conventional ideology of the time that was still fixated on the “airscrew" design of some guy named Leonardo DaVinci. Aside from his love affair with science, Unaipon became the first Aboriginal writer to ever be published, and he travelled extensively throughout Australia arguing for better treatment for all Aboriginals. We can only wonder how much more enriched Australia would have been had he not been ignored.

While Unaipon died a destitute inventor, the irony is that he can now be found on the $50 bill, seen on billions of dollars around the country.

Pedal wireless

Lack of communications between remote stations and settlements was a huge obstacle in the early days of the Royal Flying Doctor Service. In order to find help, often you’d need to travel hundreds of kilometres to find a telegraph or telephone. With this difficulty in mind, Rev John Flynn set SA engineer Alf Traeger the task of developing a simple and affordable way for outback stations and settlements to call for immediate help.

In 1927, Traeger set up his first model, a Morse code system that used a hand-cranked generator. But that needed at least two people to operate, which isn’t always possible in an emergency. Traeger soon refined the system, offering pedal power and leaving the hands free to operate the transceiver.

Later he added a Morse keyboard, making Morse knowledge redundant for operation. It didn’t take long for the new technology to be used for things other than medical emergencies. The gulfs between far distant next-door neighbours were soon sliced away and radio “galah sessions" became the norm. Traeger succeeded in not only drastically cutting down response times, but he also gave the outback a voice.