In the red dusty expanse, single-minded, eccentric and sometimes utterly insane personalities thrive. And without question it’s the people who have formed a special bond with the outback that make it so wonderful and unique. Sol Walkling looks at just a few of the amazing people out there who have made the outback what it is today.

Ian Conway

Those born into the seemingly inhospitable wilderness hundreds of kilometres from what most people would consider civilisation consider themselves lucky and rarely leave the place. Some, like Ian Conway, have become modern-day pioneers. The son of an Arunta woman and a Kidman boss drover, Ian grew up on Angas Downs station, three hours southwest of Alice Springs. As a boy, he learned everything there was to know about camels from his Aboriginal grandmother – and transformed that traditional knowledge into his daily bread when he decided to invite tourists in for a cuppa and some bush tucker at his Kings Creek homestead to share his love for the land.

Today, the outback camel station and eco lodge owner is the leading exporter of camels in Australia (he also co-founded the Camel Industry Association), plays host to regular documentary film crews as well as tourists and has even retraced Ernest Giles’ steps on his favourite camel, Atwa. It mightn’t seem like a traditional life, but Ian considers himself a keeper of the land – here to look after it until he’s gone – like those before him.

Robyn Davidson

Tracks, A Woman’s Solo Trek Across 1700 Miles of Australian Outback, is the title of a travelogue by this adventuress extraordinaire, whose story also involves camels. Her preparations and taming of the temperamental animals took two years, not counting the countless hours spent looking for them every morning before each day’s ride. Robyn set out on her dangerous and crazy-sounding journey in 1977 practically by herself – dog and four camels aside – to learn about the desert and its traditional owners. She came back an infamous hero who’d walked at times clothed in nothing but her own skin.

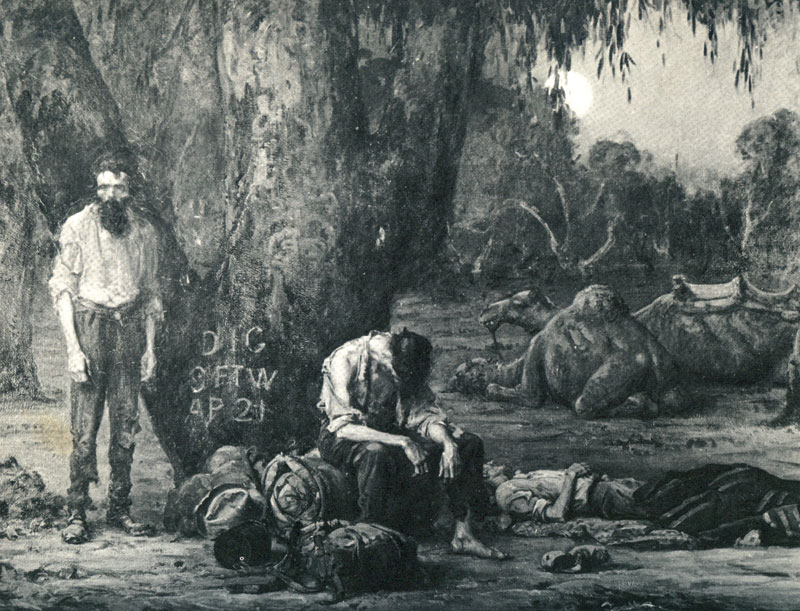

Burke and Wills

In 1860, Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills famously attempted to cross Australia from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria in order to become the first Europeans to open up the uncharted territory at the heart of Australia. Despite being pretty inexperienced bushmen, they actually completed the north-south part of the journey with their 18-strong team, before perishing on the return journey in June 1861 at Coopers Creek.

Although seven people died and only John King, who was in charge of the camels, made it all the way back to Melbourne, the expedition did serve to increase our knowledge of central Australia – and at least disproved once and for all the fanciful notion of an inland sea.

Steve Irwin

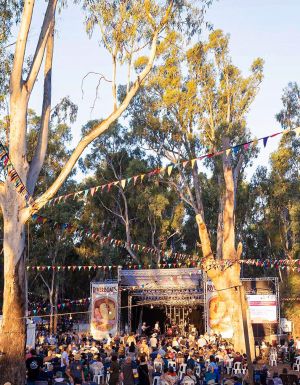

A more recent tragic hero’s death in Queensland moved the world, not just Australia. Our beloved Crocodile Hunter, conservationist and self-proclaimed Wildlife Warrior’s rare gift with animals and his larger than life personality earned him worldwide recognition. With his “Crikey" catchcry, broad smile and sparkling eyes, he captured TV audiences and sparked an interest in his conservationist message.

He died in 2006 after a stingray’s spine pierced his chest. (Interestingly, a series of suspected revenge attacks on stingrays along the Qld coast soon followed, with several found with their spine-tails severed.)

Steve’s daughter, Bindi, who seems to have inherited Dad’s sunny personality, wowed audiences at his memorial service at Australia Zoo, the family’s home, when she gave a speech in front of more than 5000 people, beginning with the words: “My Daddy was my hero." Bindi has since become a celebrity in her own right – just as her father had predicted – with her own TV show, DVD, appearances on US chat shows, and as the youngest ever front-page model for New Idea in 2006. She is also a zookeeper at Australia Zoo and continues her father’s conservation work.

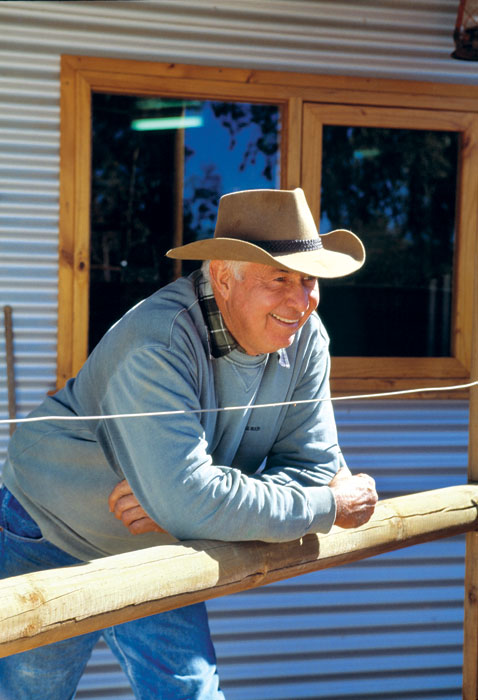

RM Williams

To survive in the outback it helps to be a jack-of-all-trades. Reginald Murray Williams was born over a century ago, in May 1908, and it was during one of his first jobs in WA – helping to establish a mission for Aboriginals – that he found the inspiration for his life: the Indigenous Australians’ mastery over their environment.

His job descriptions were as varied as the outback is vast, ranging from horse breeder to miner to stonemason, author and entrepreneur. If it hadn’t been for a chance encounter with a man known as Dollar Mick, who knew how to make pack saddles, RM would’ve likely stayed a very successful (but far lesser-known) well-sinker.

Together with Dollar, he perfected the art of boot making using only a single piece of leather, before opening a workshop in Adelaide. His skills must have been rather extraordinary as his first overseas order came from no less than the King of Nepal. In combination with a successful gold mining venture at Tennant Creek, his business quickly turned RM into a multi-millionaire. He must have been quite a sight when he staggered down the street to the bank with bags of gold, shotgun on each side. He passed away in 2003, aged 95, as the nation mourned the end of an era.

John Flynn

Born two weeks after Ned Kelly was hung, the life of John Flynn couldn’t have been more different from the famed outlaw’s. Trained as a minister, Reverend Flynn’s defining moment was his arrival in outback Beltana, SA, in 1911. Moved by the hardship of life in the bush, in particular the lack of medical help, his moving report to the Presbyterian Church the following year led to his appointment as head of its “bush department", the Australian Inland Mission.

When Flynn started his work, only two doctors served a total area of 1,8000,000km2, using bush hospitals, hostels and ministers-cum-boundary riders on camel or horseback. Faced with the problematic vast distances in the outback, Flynn’s solution came in the form of a letter from Lieutenant Clifford Peel, a young Victorian medical student with an interest in aviation.

Even though radios and planes were very much in their infancy in 1917, Peel’s letter impressed the reverend and was the first step towards the establishment of the Royal Flying Doctors Service, and today more than 20 bases span the length and breadth of Australia.