On the banks of the Murray lies a town that is surviving, thriving and drawing visitors from around the world. Considered the fruit basket of Victoria’s far northwest, Mildura’s a small town with big surprises.

The premise is simple. I’ve had it up to here with Sydney and I want a weekend away. But I want to go somewhere different. Somewhere my friends haven’t visited. Somewhere with neither casinos nor 30,000-seat stadiums.

Then serendipity occurs; I get a call from AT’s editor. “Do you fancy a trip to Mildura?"

That’s not what I was expecting. By “different" I was thinking Mudgee instead of the Hunter, Ballina rather than Byron. But this could be perfect. Or a disaster. Some research is required before I go, but a quick trawl of the interwebs leaves me more confused than ever. I discover that Mildura is a big town (pop 30,000). It even has a university. But I’m concerned since its main claim to fame appears to be that 95 per cent of Australia’s dried fruit is produced there. Klaxons sound in my head. If your main claim to fame is sultanas, then please – send me somewhere renowned for chocolate cake. Or Wagyu beef.

Then I come across an online listing of coming events for Mildura. I’m flabbergasted. How on earth can a small town produce an events calendar for a single month that runs across three printed pages? I’m not sure even Melbourne could achieve this. There’s obviously more to this place than sultanas. It’s dark when I fly in (Rex, Qantas and Virgin Blue fly direct from Melbourne, so from Sydney I’ve sort of come the long way), but I’m able to make out enough to form some surprising first impressions. The airport is large by regional standards, with a little cafe and a very good museum. The taxi I jump into is yellow, cheery and very clean, providing me with the first important clue that, despite straddling the border, Mildura is more Victorian than New South Welsh. I’d planned to stay at the Quality Resort Mildura, but the cynic in me had its oxymoron alert switched on, so I opt for something with a more humble name and price: the All Seasons Motor Inn. Neither paying nor expecting much, it’s nearly 10 pm when I arrive and check-in. It’s simple and very clean, which is just what the doctor ordered. I need an early night for tomorrow’s big task: finding out exactly what a town that leads the field in sultana production is really like.

Surprises aplenty

It’s Saturday morning and the civic centre of Mildura, the mall, is absolutely heaving. There’s a car show on with people displaying their pride and joys. They aren’t exotic Italian machines that cost a fortune, either; they’re honest cars, renovated, polished and manicured by honest people who couldn’t give two shits about what other people think. To underline this point, a DJ blasts out some ancient rock ’n’ roll so that a group of middle-aged women with paunchy partners can show the kiddies how dancing was done in the ’50s. I’m flabbergasted. The women wear pink wigs. Where on earth have I landed?

Suddenly there’s a commotion. Hundreds of teenagers are screaming and I realise not everyone is here to see a hip-grinding display by a group of people not far off needing new ones. Half the crowd is actually an enormous queue to meet some visiting Home and Away stars, in town for an autograph signing. It’s all a bit much, so I decide to grab some breakfast. With the one other major fact I’ve learned about Mildura firmly in mind (that it’s the home of Stefano De Pieri, famous for his Gondola On the Murray TV series, as well as various forays into the competitive worlds of Australian high cuisine and local politics), I head to 27 Deakin on the main drag. This is just one small part of Stefano’s sprawling empire in Mildura, and my breakfast is . . . okay. Not to die for, but it’s lovely to be sitting in the sun as cyclists resplendent in leggings and clip-clop shoes order coffees and argue animatedly – yet another reminder that I’m in Victoria. After paying $25 for what is a mediocre repast of coffee, fried eggs cavolo nero and pork sausages, it’s time to do some more exploring.

I consult my seemingly endless “what’s on" guide and flag a taxi out to the Sunraysia farmer’s markets. It’s a short trip, but as we emerge from the town in broad daylight I realise for the first time just how far outback we are. The land is parched, with scrubby, stunted trees vainly seeking sustenance on arid plains. Time to interrogate the taxi driver. I’m quickly informed that, yes, the place is remote. Sydney is 1000km away, Melbourne half that. The nearest town of any great size is Broken Hill, itself not exactly a bastion of civility, beaches and fine coffee. The nearest capital city is actually Adelaide, around 400km to the southwest. Yep, this place is isolated. Really isolated.

But now it’s starting to make sense. When you live in a community this far-flung, you tend to make your own fun. You have to. Mildura neither bemoans its isolation nor complains that the rest of the world is leaving it behind. It’s a stoic place, self-reliant. And so, necessity being the mother of invention, its people have concocted all manner of festivals and events to build an industriousness – a feeling of keeping busy – into the fabric of their lives. It’s that or go mad.

I expound my theory to the kind lady at the Visitor Information Centre. She stares at me blankly for a couple of seconds, then her face lights up. “That’s exactly right. We are isolated. And so we create our own events. We have a great community like that. It’s good for the kids."

Just add water

To really understand Mildura, it’s important to grasp a little of its history. Like much of inland Australia, water is everything. The Aboriginals knew this better than anyone, and in fact, Mungo Man (considered to be among the oldest remains of human existence) was discovered only an hour up the road. In the 1880s, the visionary Chaffey brothers immigrated to Australia with hopes of replicating work they’d done in California in setting up an irrigation scheme. After numerous setbacks, they were ably assisted by a creative young politician (Alfred Deakin, who would become Australia’s first PM, and after whom Mildura’s main drag is named) and were subsequently granted 250,000 acres on which to develop irrigation. To cut a long and fascinating story short, the Chaffeys were successful, and leaseholders soon developed thriving citrus, stone fruit and grape-growing industry. Unfortunately, the scheme collapsed under a cloud in 1892 and a Royal Commission was called – which found the scheme to have been mismanaged by the brothers.

William Chaffey was a true visionary, and in hindsight, four years was never enough time to get such an audacious scheme up and running. In today’s times, setting up an engineering project of this scale would take 20 years or more. An example: “Big Lizzie", a fascinating tractor (yes, that’s “fascinating" and “tractor" in the same sentence) is a monster of a machine that was used to clear land around Mildura and Red Cliffs. The place is so isolated that it took two years to drive it to Mildura from Melbourne. (Lizzie, all 45 tonnes of her, is on display in the main square at Red Cliffs about 20min south of Mildura.) Anyhow, following the Royal Commission a trust was set up to manage the assets, and William Chaffey, in a move that would be considered astonishing by today’s Christopher Skase-inspired standards, stayed in Mildura to work off his debts. Ultimately he won the hearts and minds of the locals, effectively becoming royalty, and indeed was the town’s first mayor.

Chaffey’s splendid house, the Rio Vista, is now restored and home to the Mildura Art Centre, comprising a theatre, outdoor amphitheatre and, by regional standards, a remarkably large and interesting art gallery.

And that’s the thing about Mildura. You expect a rural agrarian town with lots of big hats, 4WDs set up for shooting trips, and prodigious drinkers. Instead you get surprises. Surprises like the dozen or so proper grass tennis courts where the Davis Cup is sometimes played. Like sandy beaches on the Murray where the Australian Beach Volleyball Championships have been held. A thriving arts scene. A town that’s doing things.And food. Great food.

With irrigation came grapes, fruit and wine. With grapes, fruit and wine come backbreaking work. With wine and hard work come Italian immigrants. And that’s what Mildura got. You get the feeling that Mildura’s Italian heritage is a big part of the story, and part of what makes the place so different. The people of Mildura are passionate about their food. Walking the main street on a Saturday evening isn’t the food poisoning lottery it is in some country towns. It’s like a scaled-down Lygon Street Melbourne or King Street Sydney. There’s a proper Indian joint, a Turkish restaurant, a Spanish tapas bar and even a decent looking Thai. Sandwiching these exotic cuisines are a battery of Italian eateries and pizza joints. It really is quite surreal.

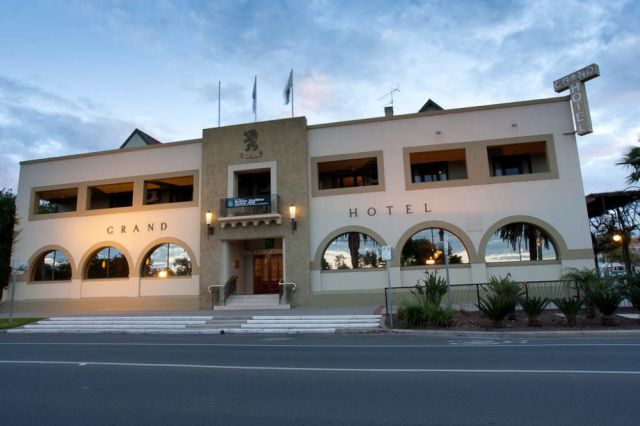

Grand Stefano

The Godfather of these Italian establishments is the Mildura Grand Hotel and its patriarch, Stefano De Pieri. So I book myself in for a couple of nights. It’s an enormous place, taking up an entire block in the centre of town and overlooking the Murray. It has four restaurants and several bars, but at check-in, I’m hoping to score a seat at Stefano’s famous eponymous eatery. It has a renowned fixed menu, where you’re served what Stefano decrees to be the best local produce of the moment, prepared in a simple Italian style. Reception calls the restaurant, but alas, I’m informed they only have a table for four left and don’t wish to turn it into a table for one. That’s fair enough, so I go off to explore the hotel. My room is surprisingly good. For $128 I get a modern room that’s well-appointed and recently renovated. It has a slightly corporate feel to it, but that’s not a bad thing. The Grand obviously caters for a lot of business guests and the rooms are large, with a wide bathroom, excellent beds and everything you could want, from wireless internet to a well-stocked bar fridge. It’s better than a lot of 4.5 star hotels in capital cities.

With my spirit crushed due to my lack of foresight in booking a seat at Stefano’s, I opt for a counter meal at one of the hotel bars. A mixed grill. For six dollars. I can’t believe it. The Scotsman in me is so excited that I immediately text all my friends with photos of my six-dollar dinner. All those posh people downstairs having one of the more memorable meals of their lives, and here I am upstairs having one of the more memorable meals of my life, watching rugby on TV and washing everything down with beer. It’s made my night. I am a happy man. And that’s another thing about Mildura. It’s just not what you expect. It really isn’t a place. It’s an experience