Franchesca Cubillo is a Larrakia, Bardi, Wardaman and Yanuwa woman from the Top End of the Northern Territory. With more than 30 years’ experience in the museum and art gallery sector, including at the National Gallery of Australia, she is currently the chair of the Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair Foundation, and executive director, First Nations Arts and Culture at the Australia Council for the Arts.

Here and now I have seen a growing interest in Indigenous art throughout my professional career, a change from looking at Aboriginal art as ethnographic and anthropological to seeing it as fine art. And that really is life-changing. Across a very short period, the market has just increased exponentially in terms of its appreciation, in terms of the economic investment. But also what you have is this increase in the amount of remarkable art being produced.

Nowadays Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists are part of our national identity, where millions of people actually come to Australia and have exposure to Indigenous culture via art. It is now at this remarkable place where I think Deloitte estimates that between $150 to $200 million is generated through Indigenous art. The Productivity Commission is doing its own research, and they say between $300 to $500 million is being generated.

Centres of excellence

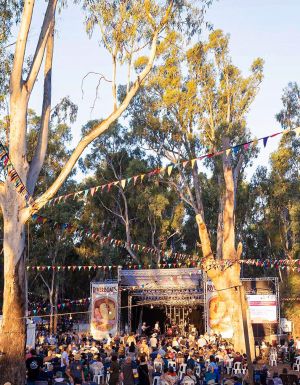

The fairs, like the Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair, are another layer in which the Art Centres, the artists, the First Nations staff can start to engage with the sector and represent themselves. Obviously there are commercial galleries that are non-Indigenous, there are collectors, there are auction houses, but Art Centres are really these amazing organisations that are small micro business, and they have been in place for at least 30 years. But we equally don’t have very many Art Centre managers. Lots of artists, which is great. We have this remarkable wealth of imagery coming from these Art Centres, but we don’t have as many First Nations people involved in that secondary industry; small business operators or curators or conservators.

What we found at the Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair is that there would be a good majority of people who have never purchased Aboriginal art before and/or had any exposure to Indigenous peoples and their culture. There is that element of people just not having the opportunity. I think a lot of art is on display in our state galleries and our museums, but they are not understanding or knowing where to go next, or how to engage. An art fair brings it to their attention, and because ours is very much Art Centre-based, it means they’re buying directly from artists and the money is going directly to them. I think non-Indigenous people are just not aware of how to engage or where to engage.

A truly Australian art

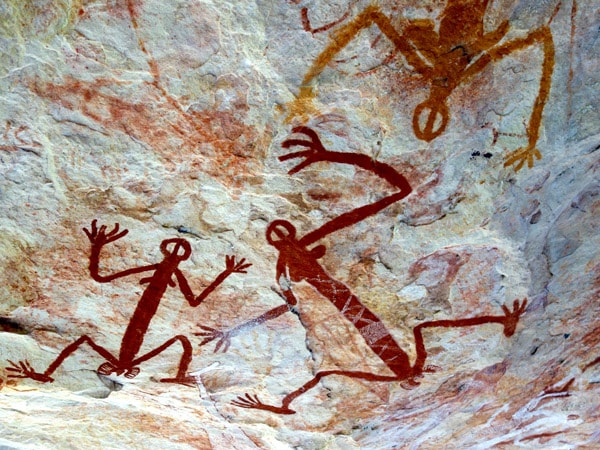

At its core is this remarkable art that really defines who we are as Australians. But it’s even more than that because it’s so connected to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and language and Country. If you were to look at [Arthur] Streeton or Jeffrey Smart – Australian art – and say ‘that is so much about us as a nation’, I think there is a small element of that, but in a global conversation [that kind of Australian art] doesn’t stand out. Whereas Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art does stand out because it doesn’t operate within a Western art aesthetic. The value systems are totally different.

If you’re an Aboriginal person from the Yirritja moiety in north-east Arnhem Land, you can only depict certain Dreaming narratives, and you can only use a particular clan design and cross hatching to depict that ancestral story. There are guidelines, there are cultural considerations and protocols that determine what an artist will paint and how they will paint. It’s so unique stylistically. It comes from a different cultural trajectory, and the aesthetic itself is so different in a global context.

I’ve been thinking an awful lot in terms of [seminal Utopia artist] Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Her practice was very much, ‘this is my Country, these are my ancestors, this is me fulfilling my obligation and I will always paint this same story because that’s my value system’. Having travelled a little bit overseas with Indigenous art, I’ve noticed that there has been this growing appreciation.

When the Dreamings exhibition went to New York [in 1988], it was seen as something very new and very dynamic. And you had some major American collectors who just got really switched on and said, ‘This is the next best thing. We can’t believe something as remarkable as this and as new and fresh exists.’ There’s still a bizarre, delayed appreciation value system, which is really interesting because Steve Martin is buying, Beyoncé is buying.

Listen and learn

I am still talking to Aboriginal young people who say, why isn’t our culture taught at school? If history is not being taught, if the art’s not being taught, the only exposure people are getting is the extreme, the bad news story. Closing the gap, the intervention, deaths in custody. They’re getting all this negative news so there’s a real fear. If you had grown up in south-east Australia living in the western suburbs, your notion of Aboriginal art is very different from an Aboriginal person growing up in Darwin totally surrounded by culture. I think the normal, average person on the street is fed a certain perspective on Indigenous people and their art and culture.

Therefore, there is a lot of confusion and uncertainty about how to engage. And of course, [it] all comes to a head when it’s Australia Day or it’s Invasion Day or it’s NAIDOC Week. So I think there’s still quite a bit of push and pull happening in Australia, but at the same time you’ve got this international push back. And a museum in Brussels has just opened with a major Indigenous art exhibition [Before Time Began at the Art & History Museum].

So Indigenous art is being seen across social media in Australia being celebrated in Europe. It must be quite difficult for a non-Indigenous person looking at it and trying to figure out what’s going on. It is a part of who we are but there’s such complexity to it.

A modern vision

Cultural exchange always happens, so this notion that something is authentic and somehow becomes detracted once it starts to take on a hybrid form is a false understanding of what culture really is.

I think in terms of art and language, what I’ve always tried to encourage First Nations artists and different regions [to do] is for everyone to be very mindful that their designs and patterns are really unique from where they come from, so that you should look to your own ancestry in terms of the patterns and the designs if you want to maintain your connection to that region through your art practice.

But equally as an artist if you want to paint in your own style, then you also should be able to have that flexibility to find your voice, find your style. And it could be like Trevor Nickolls [described as the father of urban Aboriginal art], you go to art school in Adelaide, and paint the way you want to paint. Really, as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person, you should be able to represent your own story, whatever it is.

A gift given generously

I think we are very lucky that art is a really accessible mechanism to engage. And to a certain extent, I think this is why political art by Indigenous artists isn’t taken up in the same way that more abstract forms like Western Desert or bark paintings are. There are more people buying those classical designs than there are buying contemporary works that are really political and blatantly advocating for social justice or land rights. But the strange thing is that those Western Desert paintings are actually title deeds to Country, so they are quite political but not in a form that is challenging. It’s quite subtle but culturally explicit.

Art has been the vehicle that has really allowed Australia to take on Indigenous art and culture as part of its identity. It is the art that has really been the vehicle that has allowed an appreciation for First Nations people and their culture.

I think for the wonderful things that art has done, there’s still a huge degree of fear, anxiety, hesitation and real resistance to letting go of control and power when it comes to First Nations people having a voice within Australia. I think the push and pull is still always going to be there.

[Culture and art] is a gift that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people bring to Australian society and to the identity in a global context.

How to buy Indigenous art ethically and responsibly

Researching and buying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art is a joy, whether you are a serious collector or a complete novice. The colours, patterns and cultural significance contained in everything from bark panels to large-format canvases to weavings and carvings are reflective of ancient traditions passed down through millennia, as well as the particular stories and experiences of the artists who render them.

Buying Indigenous art in an ethical and responsible way not only pays respect to the significance of this ancient form – said to be ‘Australia’s greatest cultural gift to the world’ – and the talent and truths of the artists themselves, but it also assists with positive and lasting economic and social outcomes.

For this reason the Indigenous Art Code was developed to preserve and promote ethical trading in Indigenous art. The code outlines established standards for dealings between dealers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists to ensure fair and ethical trade in art, transparency in the promotion and sale of artworks, and that disputes are dealt with fairly.

Whether you are buying from a gallery, at auction or from a dealer, the Code advises you ask lots of questions, including: who the artist is; where the artist is from; how the seller acquired the artwork or product; how the artist was paid for their work; how are royalties or licensing fees paid to the artist in the case of reproductions; and, importantly, is the gallery a member of the Indigenous Art Code? If the answer to this last question is yes, then you know that it has agreed to follow the Indigenous Australian Art Commercial Code of Conduct.

Of course, buying direct from artists, by visiting Indigenous owned and operated Art Centres or attending ethical events like Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair (DAAF), is possibly the best way to learn about and acquire Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art, allowing you to form a relationship with the artists themselves and better understand not only the art form but the stories and experience imbued in the pieces being generously offered for sale.