NSW’s Lake Mungo mesmerises visitors with its otherworldly beauty and astounding ancient history. It has set the scene for megafauna, for meeting tribes, and for some of the world’s most incredible archaeological finds.

WINNER OF THE ASTW Best Australian Story over 1000 words of 2020

The cordial countryfolk have learned to identify the strangers by their transport. Not what they arrive in exactly – lustrous all-wheel drives – but by what they carry: a kayak on the roof racks perhaps; maybe a jet ski lolling behind; pool noodles pressed up against the rear window like a kidnapped rainbow.

And then comes the question, incredibly, that locals swear they are asked often: “Not much water in the lake at the moment?"

The unenlightened pleasure-seekers are politely schooled on the reasons why they won’t be able to go for a paddle in Lake Mungo today. Or tomorrow. Or even this time next year, rain or no rain.

Turns out they are about 10 millennia late for a dip, give or take. That’s estimated to be when most of the now World Heritage-listed, 240,000-hectare Willandra Lakes region permanently vaporised. Eighteen thousand years ago would have been even better for them; that’s the last time the now-fossilised Lake Mungo was in full flood – a Pleistocene jet skier’s wet dream.

To be fair to the aforementioned out-of-towners, even all-knowing, all-seeing Google Maps disseminates digital disinformation, ‘blueing out’ Lake Mungo like it’s a colossal water-ski park.

So why drag yourself to an outback ‘lake’ that’s not? Well, just as swiftly as local knowledge and common sense dismantle the fable of a great inland Wet’n’Wild, science, Indigenous lore and unrestrained natural splendour rebuild it as something infinitely greater: a barely explicable epiphany that’s been described as a ‘bookend of humanity’, which has miraculously escaped the greater consciousness of mainstream Australia, for the most part. So let’s dive in, shall we?

Epiphany in the expanse

Despite its middle-of-nowhere aura, Mungo is only a few hours’ drive from the Little Smoke: the city of Mildura. Yet the city’s Darling-River-slaked orchards, vineyards and tilled fields swiftly transfigure into confident outback greys, browns, khakis and reds.

This landscape requires its beasts to be robust, resilient. Headstrong feral goats, too tenacious and nimble to become roadkill, munch on dystopian thorn bushes; hulking red roos lay prone under rare and cherished shade.

Approaching the national park, the mallee scrub squats down low. Gumbi gumbi trees (bush apricot) and black saltbush kowtow, like a warm-up act walking behind the curtains so the superstar can shine. Technology concurs: “no receivable stations", whimpers the confounded self-tuning car stereo.

Parks and Wildlife could have shaved a few bucks from its budget by ditching the ‘you’re here’ signs. Sensitive souls sense the epiphany pretty much exactly where the barely-above-sea-level national park begins. Something shifts; even by outback standards, the open expanse is trippy; it instantly bewilders,

and infuriates eyes accustomed to order, reason and context.

“This was a meeting place," says Mungo National Park ranger Lance Jones. “You would travel for months and months, when the season was good, when there was plenty of water."

Willandra Lakes is indeed the junction of three massive ‘countries’: particularly, those of the Barkindji (Paakantji), the Ngyiampaa and the Mutthi Mutthi. Every tribal group of the Murray, Darling and Murrumbidgee rivers connects to this place in some way.

According to the latest science, Mungo is pretty much at the epicentre of Australia’s cultural chronology, home to the oldest human skeletons ever found in Australia – and some of the oldest found outside of Africa.

If you haven’t already made their acquaintance, it’s probably a splendid time to meet Mungo Man and Mungo Lady. The story goes that geologist Jim Bowler ‘found’ Mungo Man and Mungo Lady on a research trip that wasn’t exactly expecting to find human remains. The good oil from local Indigenous communities, however, is that the Mungos actually ‘found’ Jim. They had a thing or two to tell the scientific community, and the world, about Australian history.

Mungo Lady was uncovered in 1968. Her remains were found to have been ritually cremated: burned, pulverised, burned again, then liberally covered with ochre. Less than half a kilometre away, Mungo Man (uncovered in 1974) was buried with his fingers interlocked, the body also sprinkled with red ochre.

For a fair while, the remains were ballparked between 30,000 and 60,000 years old, until 2003, when the CSIRO and three universities concluded the Mungos to be more than 40,000 years of age. Which was, and is, a huge deal in this continent’s scientific and cultural story.

Why? Well, the pair (who weren’t actually a couple, by the way) are said to be the earliest examples of complex and ceremonial burial yet found, anywhere on Earth. Giving them an age effectively doubled the length of time that science could prove Indigenous existence in Australia. It was a sophisticated existence, too, compared with much of humanity back then. Other artefacts found in the area helped date Willandra Lakes’ human occupation to around 50,000 years ago.

All of which was no newsflash to the Barkindji, the Ngyiampaa and the Mutthi Mutthi, but the events didn’t really grip the Australian imagination as much as they should have, according to author Thomas Keneally.

“[It’s] an Australian phenomenon, a world phenomenon: the first ritual burial of a human, 42,000 years ago," he told the BBC. “He was adorned with ochre that came from two hundred miles away. Implements were used that came from way up in the Australian Alps.

“I just want Australians to know that there were Australians who were a living concern, and living well, two ice ages ago. That’s our history, spiritually at least."

As happened with many 19th- and 20th-century ‘discoveries’, the Mungos were unceremoniously whisked away ‘off country’, all in the name of science and with scant regard for the cultures concerned.

“These are our ancient cemeteries, our ancient burial ground," said Mutthi Mutthi elder Mary Pappin in 2015, when Mungo Man was formally returned to country (Mungo Lady was returned in the 1990s). “We hold [the lake] very dear to us because we know our old people are sleeping there. Taking the bones away to the city is taking that person away from their spirit."

It was a wrong that was even acknowledged by Jim Bolger himself: “There was a lot of hurt caused to the Aboriginal people. We owe an apology to them for what science has done."

Nowadays, you can’t meet the Mungos face-to-face, so to speak. They, along with more than 100 sets of remains of varying ages, are locked away somewhere near the Mungo Visitor Centre, a place where the area’s complex, often-competing histories of both black and white is told thoroughly and thoughtfully, especially at Mungo Meeting Place.

“The elders are the only ones who see them now," says Lance. “They are talking about [finding] a ‘keeping place’ near where they were found, but the public won’t be able to go near it."

To be a Mungo ranger, to be able to tell this country’s story, you must descend from one of the three tribes. Lance is clear that he only relays the experiences of his own people – one third of Mungo’s Indigenous saga, selectively passed on to him by elders. Yet for all their differing stories and totems, Willandra Lakes’ three tribes share a troubled modern history.

The Mungos’ return was a watershed moment in a healing process that was parched. “I was part of the Stolen Generation," says Lance, who was raised in Broken Hill – Barkindji country, a mere 330 kilometres away. “It makes me feel good to work on my grandmother’s country. The culture is returning, too. I do a bit of artwork, ostrich eggs and other things [featured in nearby Mungo Lodge’s lobby].

“I’ve been involved in the handback of two other national parks, and I was there the day when Mungo Man got handed back. That felt really good."

Peeling back the layers

For most visitors, the huge park’s hypnotising focal point is the incongruously named Walls of China: wrinkled pinnacles of dried mud that resemble bonsai mountain ranges emerging from the earth like clenched cold-water-pruned fingers.

The walls crown ‘lunettes’, sand and clay layers furiously cast and recast by perpetually flurrying winds from the flat lakebed. Named for their resemblance to the puissant crescent moon, the lunettes are unwitting time capsules, opulent with artefacts because Lake Mungo was a ‘terminal basin’ with no outlet. A giant sink with the plug in.

Archaeologically speaking, the three layers – Gol Gol, Mungo and Zanci – are almost self-peeling onions, with the ground, especially the Mungo layer, desperate to share another tangent. Much of their original structure has been eroded away, accelerated by European settlement: rabbit plagues, over-grazing, the usual suspects.

In 2003, yet another world first passed us by with barely a headline, when Earth’s largest collection of fossilised Pleistocene human footprints was uncovered.

The 20,000-year-old marks in the claypan are said to be those of hunters. Among them, the footprints of a child and possibly a one-legged man, too. The delicate marks, like much of this precious history, were re-covered with sand back in 2006 to preserve and protect them – there are replicas at the information centre.

Doctors Seuss and Dolittle combined could not conjure up a menagerie as unlikely as the one that has roamed Mungo over the ages. Willandra Lakes was a prime megafauna stomping ground; we know this because of the prevalence of evidence such as Genyornis eggshells (two-metre flightless birds) and Procoptodon bones (a giant kangaroo with a stout-nose).

The remnants of more familiar animals hint at how different the lake and lakeside once were; bits and pieces of hairy-nosed wombat proliferate alongside almost infinite otoliths (fish ear bones). Curiously, a couple of pretty famous Tasmanians hung around this part of the New South Wales outback until relatively recently, too, with evidence of both the Tassie Devil and the Tassie Tiger.

But that was then and this is now. In between, the Mungo-scape has been radically modified by an ice age and possibly a water flow-diverting earthquake. It’s so difficult to imagine what even the most grand-intentioned pastoralist saw in this rain-shy baldness less than two centuries ago.

The interior’s relative merits were no mystery, thanks to the efforts of explorers Burke and Wills, Charles Sturt and Thomas Mitchell, who had all passed through the greater region before cattle stations like Gol Gol were established around 1860. They were still ploughing on in the 20th century, when Mungo Station reportedly received its name from the eponymous patron saint of Glasgow. A greater geographical juxtaposition surely cannot exist.

The 70-kilometre, unsealed Mungo loop track (combined with the Zanci Pastoral Loop) shows you every hurdle that hope-filled farmers faced in their attempts to subdue the unsubduable, fence the unfencable. All that remains of Zanci Homestead stands as an outdoor museum of human optimism: rough-hewn, thick-trunked cypress pine sheds and sturdy yard fences; a stone chimney that’s lost its room; a lonely, outdoor thunderbox, the punchline to a joke that no one remembers.

Further around the loop, Sahara-esque sand dunes, shifting ever eastwards, stand guard over the remnants of Cobb & Co coach wheel ruts not too far from wildlife-magnet Vigars Well.

That was then, this is now

Now that Mungo’s a national park, the impose-yourself-on-the-landscape paradigm has been swapped for a strategy of appreciation and management, in what is actually quite a fragile ecosystem.

“Back in the 1950s, people used to holiday and drive on the lunettes," says Lance. “Now you can’t go off the path unless you’re on a tour, but we’ve seen arrogant and ignorant people with motorbikes and drones up there. It’s very hard to police."

The majority of people who travel out this way willingly heed the don’t-be-a-dick philosophy these days, and there’s a growing appreciation of the environmental effervescence of the arid zone, a place that to the uneducated and unwilling eye can look like a post-apocalyptic film set.

At the day’s extremes, Mungo intoxicates like no intoxicant I’ve tried: it roots you to the spot, removes you from your life, shucks your attention span wide open again. Golden hour bounces reds, apricots and peaches off rippled and strangely dimpled ground, resurrects fossilised stumps into fantastical whims of your imagination. The science, the stories and the spirituality become more comfortable in each other’s company.

“We do sunset tours, but we don’t go up there at night," says Lance. “The private operators do them, but we try to talk them out of it. Some people say they’ve heard spirits, seen spirits, heard the didgeridoo, and laughing. It’s a very spiritual place of which you only see barely a fraction."

Perhaps Lake Mungo is not as colossal in this country’s imagination as it could be because we have disregarded these Indigenous insights. Maybe words fail to describe a place such as this. It’s all there, a simple and classic Australian understatement, in the Barkindji welcome to country: “Paliira kiirinana parmiba". Our country is beautiful, please come. Just leave the pool noodles at home.

Details

Getting there

The closest major centre to Mungo National Park is Mildura, between two and three hours’ drive. Whichever way you drive, you will inevitably encounter unsealed roads that are usually in good condition. Always check road conditions and carry adequate food and water.

Touring there

Guided walks around the Walls of China with NSW National Parks and Wildlife Indigenous rangers can be arranged at the Mungo Visitor Centre (July through October).

There are a variety of tours that also cover the wider park, such as Balranald-based Outback Geo Adventures.

Staying there

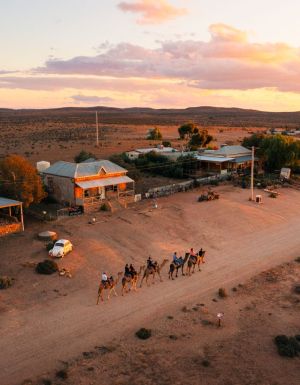

Mungo Lodge is about 15 minutes’ drive from the Mungo Visitor Centre. On a sprawling 77-hectare property, the lodge is well appointed with large rooms, a restaurant and a cosy bar area.

Flying there

A scenic flight gives a sublime contrast between the creamy, wide lake bed and the surrounding red dirt. Hangar 51 Airtours can pick you up from Mungo Lodge, Wentworth or Mildura.