Myth has it that Kakadu is best visited during the calm and cloudless dry season. But intense weather seeds surprise, adventure and new life. We go in search of the soul of Kakadu in Wet Season.

When rain starts falling on Kakadu, it’s as if a sky-bound Buddha has broken his prayer necklace, sending delicate, clear beads dancing over the hills, dirt tracks, rivers and billabongs.

Next, the wind picks up. It inhales and exhales with force. Colours shift in the sky. Blue tones turn steely.

Then, when things get real, lightning percussion booms and the main monsoonal act arrives. Rolling sheets of water break like waves, colliding mid-air and crashing southwards – and, as it happens, across my head and shoulders.

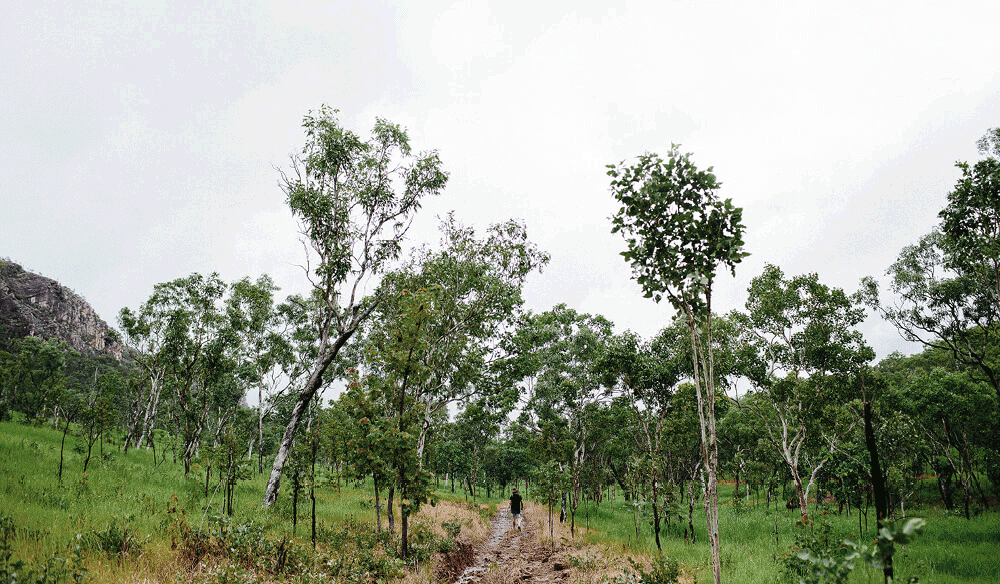

I’m midway along the 7.5-kilometre loop walk to Motor Car Falls in the southern part of the park. I’m soaked and quietly freaking out about my camera getting drenched, despite its position six layers deep in my backpack. But I feel high. Ecstatic even. What’s wrong with me?

During the wet season, which descends on the Northern Territory’s Top End between November and April, Kakadu National Park – 150 kilometres east of Darwin – is inhospitable.

Or so the grapevine holds.

This idea has clung to the collective travellers’ consciousness with tenacity. Roads that cut through Kakadu, Australia’s largest terrestrial national park, are clear, hotels yawn with extra space, and friends further south sound perplexed when I tell them where I’m headed. “Isn’t it rained out there? Is it even open?"

Kakadu, in fact, stays open all year round. And while access to some sites is affected by rain and many waterholes remain un-swimmable, there’s no shortage of things to do while those prayer necklaces in the clouds sporadically scatter beads.

I’m here to scratch at the adage that the park is a lesser beauty in the wet than it is during the dry season and discover what holds true.

Prior to hitting Kakadu’s walks and waterfalls to find answers for myself, however, I put a call in to one of the park’s Indigenous traditional owners. “My name is Bessie Coleman," she says. “I’m a bush baby and I speak for three clans in the southern part of Kakadu. These are the Jawoyn, Bolmo and Matjba."

Bessie is in her early sixties. She’s one of 13 siblings born at Old Goodparla Homestead near Kakadu’s Yellow Water Billabong. When we connect, Bessie has just come inside after being out with rangers. Given all the rain around, new flora has sprung forth and the team is busy wrestling with weeds. “We look for plants that are not native," she says. “We find gamba grass, bellyache bush and rubber plant – that last one has thorns that can cut your feet if you walk on it."

As well as weeding, during the wet season Bessie fishes and takes walks around Motor Car Creek, usually with a male relative to guide her. There’s rock art in the area’s hills – “men’s business," she says – and women have to be careful to steer clear. Luckily, there’s plenty for her to see on ground level. This time of year, she says, is her favourite time of all.

“When the wet arrives, Kakadu comes alive," she says. “There are animals everywhere. Wild berries, plums, bush potatoes and little fruits come up – red apples, white apples, everything comes alive. When the storms come, they clean out all the creek and river systems. Then the fish come up."

I ask what she’d say to those travellers who only want to visit during the dry. Bessie answers firmly. “I’d tell ’em they’d be missing the best part."

Walking in waterfall country

Recalling her words a few days later, as I stand soaked and stressed about my camera, I have mixed feelings as to whether or not she’s right. A parade of gnarly horse-flies have feasted on my legs, my hat is heavy with moisture and I have a kilometre or so to go until I reach Motor Car Falls. I look for cover. There’s none to be found.

Frankly, I’m surprised. I expected Kakadu, especially in the wet, to be one dense thicket of trees and grass – genuine, proper jungle.

“You OK there?" shouts a passing traveller. “Will be once I reach the falls," I reply, wiping my sunnies to see him. Pete is from Alice Springs. He’s staying at Cooinda Lodge, located on Yellow Water Billabong.

“Yeah, I thought I’d be bush-bashing all the way to the falls," he says. “But instead, the landscape is so open and exposed. It’s such a super-charged shade of green, too."

He’s right. The green that engulfs us is neon. And while the walk starts on a rickety footbridge, it soon transforms into corridors of spear grass, and then into rocky outcrops flanked by hills. Though knee-height right now, the spear grass will grow taller than a human – though it doesn’t stay upright for long.

‘Knock-’em-down’ is the name given to the current season by Jawoyn people, Bessie had explained, noting there are six seasons in her calendar altogether, and this is when the grass is flattened.

I bid Pete farewell and push on to the falls. Water pools inside my shirt and my pants adhere to my skin. In the midst of all this indignity, though, there is something about the rain’s intensity that has buoyed my mood – that odd ecstatic feeling I mentioned earlier.

I’m physically uncomfortable, yet strangely at peace. The storm brings with it a reminder of nature’s might. I’m acutely aware of being alive: a realisation that’s hit at the exact moment my photography gear might be deemed cactus. Ace.

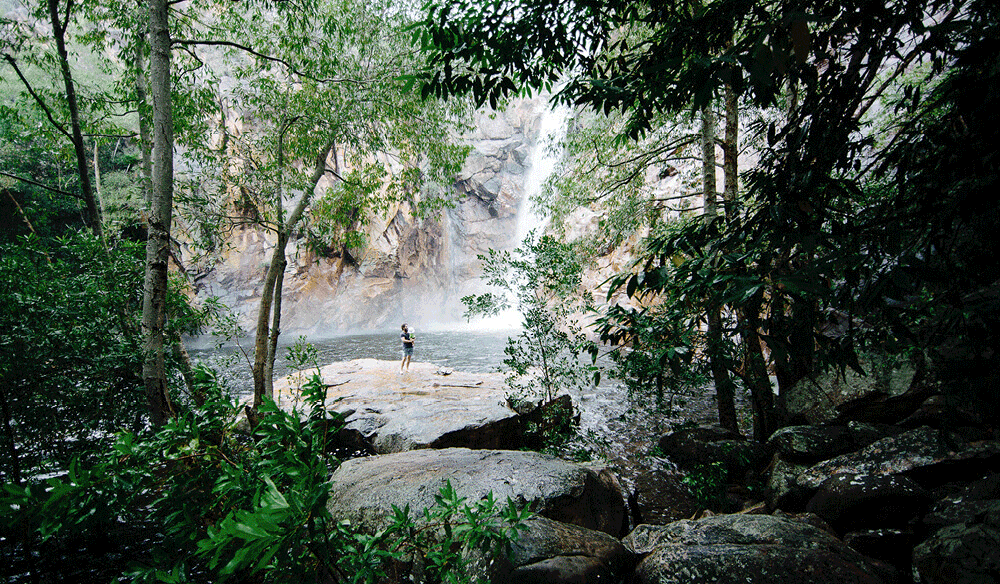

Finally, a sign directs me to Motor Car Falls. I barrel along a narrow track just as the clouds open up. “Holy wow," I whisper, stepping onto flat rock to view a fan-shaped sash of water careen down the cliff face. Mist floats off the pool’s surface like chiffon.

I imagine I’m a tiny, frozen figurine trapped in a terrarium. This spot, a million miles from urban life – and uninterrupted by the presence of other tourists – feels as if it’s a paradise lost and found.

I burrow through my backpack, cross my fingers, and extract the camera. It’s wet but it works. I take my lens off, let the condensation clear, then snap away in celebration. When I return to the trail, my sopping boots carry me back to the car park where my mind drifts to hot showers, fluffy towels and solid sleep.

Back at Kakadu’s ‘Croc Hotel’ (it’s shaped like a giant saltie), I manage the first two goals, but save sleep for later. I’ve booked a late afternoon scenic flight to better map the park in my mind.

Flying through stone country

My pilot, 26-year-old Anthony agrees with Bessie that the wet season is the best time of year to be here. “You get to see the waterfalls in full flow, and that’s pretty epic."

I assume shotgun position beside him and soon we’re gliding above my hotel. “Its ‘eyes’ turn red at night," he says, pointing to the yellow lights on the building’s roof – another kitsch flourish from the town’s resident croc.

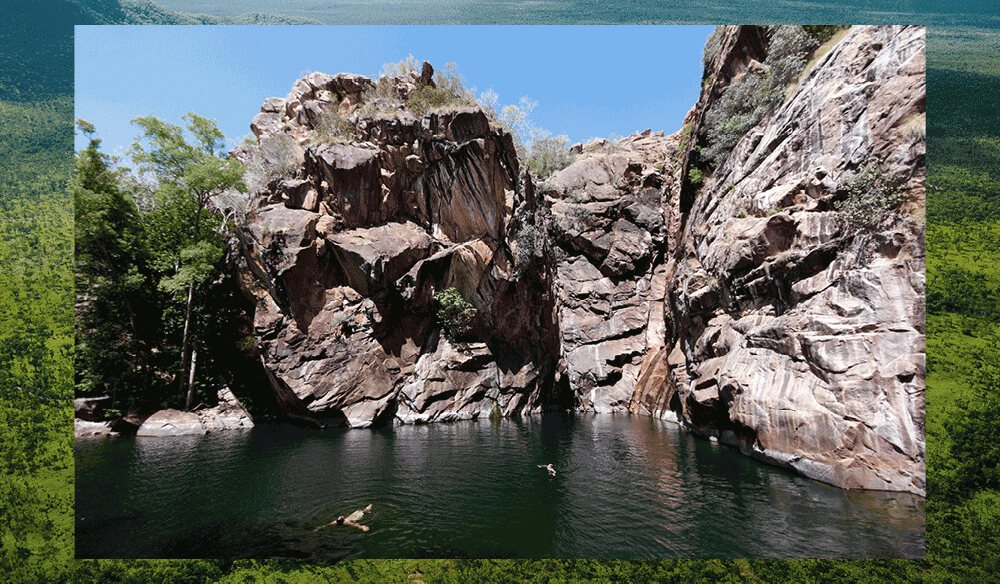

Leaving Jabiru in our wake, we trail along a green valley. Clouds cast shadows over the land in cookie-cutter shapes. Streams snake through trees that resemble broccoli florets. So far, so flat. Then the escarpments appear. In orangey coral columns, these sit tall above the country’s floor like teeth or giant thrones. They’re breathtaking. I can sense Kakadu’s seduction routine starting up all over again.

Our plane circles Twin, Jim Jim and Gunlom Falls. Each gushes white water. Over the engine noise I shout: “The park doesn’t look as wild from up here; it’s so serene!" Anthony nods and points at Gunlom, where a landing strip sits away from the falls – built to accommodate the Crocodile Dundee film crew.

I’m reminded of my chat with Bessie. She’d mentioned that very crew and said they respectfully worked with Kakadu’s Indigenous elders. “We want more movie-makers to come and see our beautiful place, see how we do things," she’d said.

Our plane heads north to stone country, where the escarpments again shift in appearance.

They’re lumpy and sculptural. Tear-shaped boulders balance beside crumbling rocks shaped like fingers. Again, I’m struck by the fact Kakadu contains all six of the Top End’s ecosystems: as well as stone country, there are wetlands, savanna woodlands, tidal flats, hills and basins, and floodplains.

We drop down to the ground, and soon, when the croc hotel’s eyes flicker red, I drop into bed. It’s a good thing I do. At 5:15am, the alarm sounds to ready me for the final leg of my wet-season exploration mission: a sunrise cruise at Yellow Water Billabong, 30 minutes south.

Cruising in wetlands country

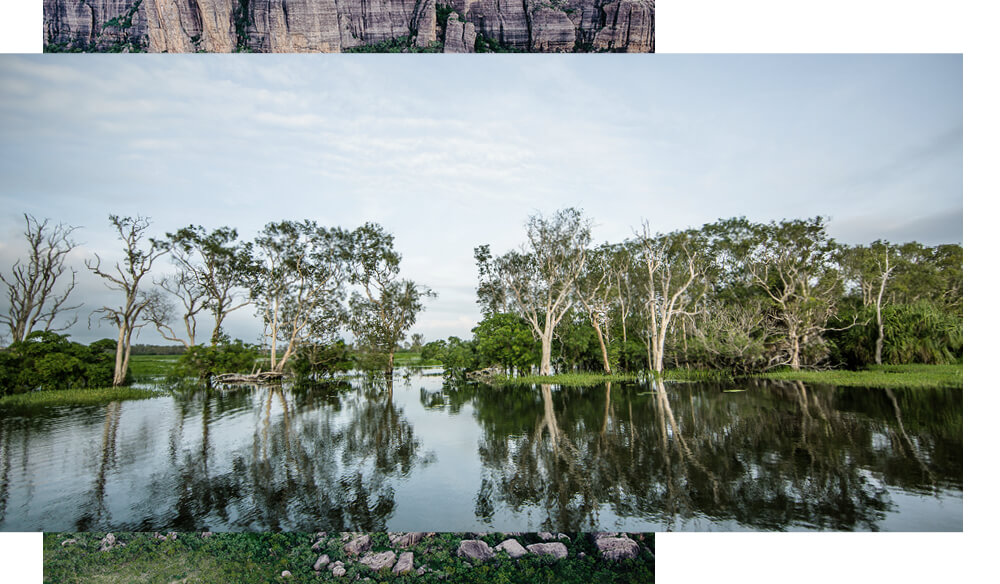

The sight of the creek – a calm, ice-blue mirror that on its face reflects paperbark trees – dissolves any residual resentment about my early rise. Local cruise captain, Donny, is the son of a traditional owner. “See those teeth marks on the buoy over there? They’re from crocodiles. Let’s just say I recommend you all stay in the boat."

He steers us into a paperbark forest. Branches poke into the cabin and things start to feel intrepid. A freshwater croc slinks by, and, at last, I see the Kakadu I’d first imagined: my waterlogged jungle, a tangled mess of branches, beasts and nests.

As we exit the forest and enter the plains, steely clouds collect above. “The rains are coming," Donny says wryly. The sky loses colour, the paperbarks bend in the wind and the water’s surface grows spiky. A sea eagle and two jabirus glide past en route to more peaceful territory.

As fellow passengers coo in delight, I put my camera away. When I do, Bessie’s voice is with me. “In wet season I love just to sit and look at the lightning, waterfalls and systems," she’d said. “People want to see breathtaking things here, but remember to listen to the stories, too. Respect the earth, the country and its spirit. See birds and wildlife. Be quiet and watch."

I’m still. My eyes and ears are open. And as more prayer beads begin to dance sideways into the boat, I know I’ve fallen for wet season – with all its mad, monsoonal magic.

Kakadu in the Wet Season details

Getting there: From Darwin, drive 250 kilometres east along the Arnhem Highway to Jabiru in the park’s northern corner.

Playing there: Kakadu Air and The Scenic Flight Company operate scenic flights during the wet season. For a complete list of scenic flight operators, check out northernterritory.com’s Kakadu Scenic Flights page .

Yellow Water Cruises offer year-round cruises through Yellow Water Billabong wetlands.

Staying there: Bed down at Jabiru’s 100 per cent Indigenous-owned Mercure Kakadu Crocodile Hotel , shaped like a giant saltwater croc.

More? Check out our Kakadu FAQs for the more on the wet and other tips and tricks

For more information on things to do in the NT, visit the official Northern Territory website at northernterritory.com