The striking animal forms, chants and motions of the Laura Aboriginal Dance Festival are as relevant now as they have been for tens of thousands of years. It’s only every two years, but here’s why you need to plan for the next one.

At the precise moment her uncle died, an owl perched itself on the back fence. It gazed through the house like an X-ray. Come dawn, it would fly away to wherever owls spend their sleepy days, returning to the same spot every single night. Nothing, it seems, would budge the owl. Not that Tamara Pearson wanted it to go. She knew what or, more precisely, who the owl was.

Tonight, Tamara is an owl. Not that owl; not exactly. She scratches sharply in the dusty earth, flutters in and out of feverish shadows that have a life of their own thanks to a palpitating light show.

Her freaky, folkloric get-up sentences the uninitiated pre-schooler to a childhood of night terrors. But the children of Cape York Peninsula’s Aboriginal communities who flock around the Laura Dance Festival circle tonight – way, way past their bedtimes – do not fear the owl. They know things; things that this white fella does not and most likely never will.

Tamara is principal for Cairns-based Sacred Creations Dance, four outback hours’ drive away. She’s not competing in the daytime inter-community challenges, but has the daunting task of providing night-time entertainment at one of the most important cultural events in Australia. Her deputies are an amalgam of her nieces and a mob of Laura town’s progeny “who’ve never really got the chance to dance at their own festival".

It’s almost impossible for an outsider to truly grasp the minutiae of Indigenous dance, culture and spirituality in a few days, but if you have the chance to do it anywhere, that chance will come at Laura’s festival.

For a start, some things simply aren’t supposed to be seen or heard by the outsider. That’s the way it is and will always be. But mostly, the modern does not want to – or cannot – see the ancient; too entangled in unbending prisms of understanding strictly scientific notions of time, space and biology. If you can’t see past these rubrics, then you really have little chance of ‘getting it’.

“Obviously, the owl is very special for me," Tamara says, with her scary owl mask removed. She is connected to the Cape on both sides of her family; her ‘people’ from Hope Vale, just north of Cooktown. “It’s a sign to say that the people who have passed on are still with us. He/she is a very wise animal that holds the key to secret knowledge and holds an ancient culture within its wings. It’s the totem for some people too and helps us to remember to show respect to the caretakers of the land," she says. “Remember, our Dreaming stories are mythical, literally like a dream. We might not actually see it, but we truly believe it."

And there it is, the epiphany; a lens with which to view the performances that unfold over the decades-old three-day festival, no matter the community, the flora, the fauna or the unseen being in focus. You see, each of the 20-something mobs who compete at Laura have their own stories, totems and, often, language; mostly distinct but also with profound harmonies, links and commonalities. For instance, while some revere the Rainbow Serpent as creator, others up this way have their own version, Mother Eel; guardian of waterholes, protector of people, yet equally a destructive force in the form of cyclones and monsoonal rains.

And that’s as good a place as any to start the story of the Laura Dance Festival.

Day 1: In search of Laura’s ‘the circle’

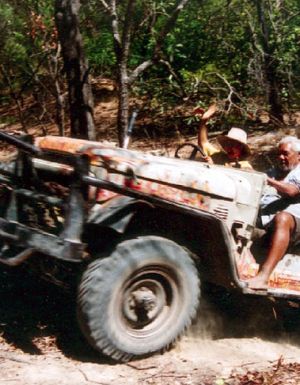

Thousands of pilgrims find their way to this isolated, intensely sacred patch of Western Yalanji territory, no more or less spiritual than the countries of the other mobs who jam into high-mileage bush-beasts and traverse immense distances to get here, over roads that would force city folk into a catatonic foetal position.

Ang-Gnarra Festival Grounds is not the kind of place you stumble upon by accident. If you’re heading north on the Peninsula Development Road you’re either on an expedition-of-a-lifetime to ‘The Tip’; visiting one of the Cape’s ‘micrommunities’; or you are hopelessly, despairingly lost. In which case, turn around and follow your bread crumbs home.

Over an indistinct rise in the road with few unnatural reference points, I catch a glimpse of a hand-crafted sign and, further into the bush to my right, a group of four proud-postured women at a trestle table, who fuss over clipboards with names on them that mean something to someone. A beefy security guard with a princely smile combs my van’s nooks. His mission: keep this sacred festival as dry as the weather is supposed to be at this time of year.

The jerky bush track into the festival grounds gradually thickens into an avenue of tents. The shade of every tree is coveted and claimed; priceless real estate to the latecomer. Beside makeshift neighbourhoods, ochre-splattered LandCruisers take a much-earned breather. I sense ‘the circle’ before I lay eyes on it; an inexplicable vitality tugs at my sweaty t-shirt, as if to say “this way". I open the door to a didgeridoo’s boundless bass, which osmotically passes through my body via a thumping eardrum that’s somehow sneaked inside my ribcage.

Dark-barked eucalypts fringe the dance ground, supervising like elders; listening keenly, raising bushy eyebrows, inwardly impressed, but wearing that eternal khaki poker-face. The circle is everything at Laura: a bush stage; a meeting place where you bump into folks you haven’t seen since last time; a classroom; and a place to simply reflect, remember, recharge and relax.

Feathered heads bob up above the human layers that trace the circle’s exact circumference, 10-people deep in places; the front-row ‘bagsed’ by fixated early-risers with fully loaded camp chairs. An authoritative sandstone ridge stands up behind one side of it, the ancient sounds that project from a tribe of stacked amps swirl around the natural bush amphitheatre freely, unencumbered.

Mob after mob mill around the hessianed-off staging area, perfectly ripe to perform, loin cloths never more vivid, body clay in the form of hands, dots and strokes never more poignant. Kids don’t know which way to look: at each other, at Mum, at the ground, yet rarely directly into the outsider’s eyes for more than a fleeting moment.

A breathy, diaphragm-popping chant drifts from performance to performance: ‘ah-hee, ah-hee, ah-hee…’ an aural relay baton, passed along the Cape’s songlines through the ages. Clap sticks crack crisply; awakening nerve-endings yet to surrender. There is simply no sharper sound in all of nature.

The Aurukun Wik and Pormpuraaw communities will dance as one today, says the announcer; sorry business (someone has passed away), apparently. A sincere silence cascades over the bush, an acknowledgement of those who never made it, gifting the absent a presence.

“We come here with a heavy heart, but we’ll do our best to give a good performance." It’s not a good performance, it’s phenomenal, solemnly intense, regenerating and hopeful, exalted by the collective will of those who watch and perhaps those who don’t.

Eventually, I slither, jostle and bluff my way into a ringside seat, and sit cross-legged in the dirt. Next, a tender, apologetic tap on my left shoulder. Wordlessly, an unbearably cute baby girl lands in my hands. A series of head jerks tells me to pass her up the line. Five sets of surprised hands in the human conveyor later, she arrives at the rightful aunty. The purest of smiles replaces her ‘which-Wiggle-are-you?’ face.

In front of me, a young girl from Lockhart River, costumed in a two-toned grass skirt, white-clay dots and a single white head-feather, gently bounces between the swaying hips of two motherly dancers; a bums-on routine refresher.

Instead of demarcating young and old in competition like some of the communities do, all generations of Lockhart River perform as one. For them, this festival is not simply a display of culture but, crucially, a transfer of it too. In anticipation of the next-dance transition, the little girl stops swaying long before everyone else does, crouches intensely, bursts into a funky emu, then sprints off into the rest of her life.

The Injinoo Dancers pay homage to every single living thing in their realm, each with its purpose; life lessons and bushcraft shared with all. First, an accolade to the bearded lizard. Apparently when you see him on the road looking “a certain way", it means big rains are coming. Next, the long-tail pigeon dance and the yam dance; the young women dig with gusto while the guys encircle them for the spoils.

During the looking-for-shade dance, a lithe and imposing older woman in a fluoro-orange t-shirt, flowing skirt and with a fluff of grey hair rushes into the circle; dancing to the beat of her own internal soundtrack, an indistinguishable style from an indeterminate era.

She kicks off her sandals and strips off her t-shirt in a fluid transition. Bare chested, she faces the crowd, who receive broadcasts about her hopes and dreams for future romance. Victorious, she bounds back into the crowd without ever becoming part of it.

Aunty Mavis receives a deferential ovation. It won’t be the last time she’ll join in, officially and unofficially. Compere Sean Choolburra reckons Aunty Mavis is “deadly". The comedian reckons everything at Laura is deadly, judging by his liberal use of Indigenous Australia’s adjective of choice.

“You walk around meeting people and practically, in some way, everyone is connected," says the Townsville local with Cape York lineage. He’s graced the stage at Edinburgh Festival, and sees parallels between the festivals.

“We Aboriginals love laughter, you can see it in our songs and dances," he says. “We always sing about funny things and always have a bit of a laugh. Storytelling is pretty much the essence of stand-up comedy. So our 40,000 years of storytelling is practically stand-up comedy in a sense. It’s about delivering a conscious message in an entertaining, humorous fashion; styling up and showing off."

Unthreatening plump raindrops briefly plop into the soil but no one legs it for shelter. As darkness cloaks the Cape, the circle disperses, back to respective campfires, via the ‘merch’ stall, which is almost pecked bare, the kids eager for the latest in flammable deadly-ware to complement their footy shorts.

The almost natural echoes of bush bands gradually fade into the darkness. Children laugh cheeky and adventurous laughs, for a while, before the third round of “go-to-bloody-bed-wouldya" hits its mark. A faraway generator eventually rattles to nothingness. A pair of ‘ring-ring’ birds ping their rings back and forth until the placid fingers of wilderness close my eyes.

Day 2: This one goes out to…

“The rubber meets the road today," says the announcer, a left-field reference to this afternoon’s finals. The festival rises slower than a goanna on the Nullarbor. The same parents who were screaming at the kids to go to sleep now bellow even louder: “You mob better get ready now… or else."

“It took us 12 hours to drive here by car," says Bamaga dancer Lindsey Mudu. “We arrived yesterday morning and had to perform in the afternoon. I was exhausted but, boy, do I feel light right now!"

He looks anything but tired, as sprightly and athletic as anyone in North Queensland. Jet black cassowary feathers sprout out of his head and legs like magical desert grass. His chest-piece displays Bamaga’s intricate traditional designs, etched into lino salvaged from an old floor.

The prop-heavy costume sets Bamaga apart from the other mobs. Lindsey’s ancestors migrated to the mainland from Torres Strait last century, when their island home became too barren to exist on. Their dance style is overtly masculine, warrior-like; complete with bow and arrow and a giant white conch on occasions. The crowd gasps as they snap their necks back and forth like a bird of paradise in fight-or-flight mode.

“We started dancing together when we were little," says Lindsey. “This is our first time here, but you can’t tell, right? We just have to wait for the finals, but it doesn’t matter if we win, really. We still have to drive back 12 hours tomorrow."

The beneficent dust swirls up and hangs in the air in anticipation. And so, as the commentator reiterates, the rubber hits the road. The circle swells, as does the pressure on performers; not to win per se, but to tell your story to the best of your abilities. Mayi Wunba of Kuranda coax the audience to join in their eagle dance. “Now I can say I danced at Laura," says a buzzing onlooker, who thought his moment had already passed. Naturally, Aunty Mavis is up again. Elon Musk could do worse than to examine her battery pack.

‘Those fellas from the rainforest’, from Wujal Wujal, execute the old man dance: decisive, deliberate thumping steps laced with aeons of attitude to show respect to the elders “who taught us everything". One of the physically biggest dancers at Laura drops to the ground like a 16-year-old Olympic gymnast. The crowd concurs it is the best goanna they’ve seen in ages. Look out Greg Inglis.

The fledgling Mossman troupe become a snake, then strut their hunting abilities. There are no elders with them today, too old to travel or unable to get off work, but the next generation is already clearly confident in their culture.

The boys and girls of Kalkadoon Sundowners dance to both morning and evening stars, then to the kangaroo, and next to the men who collect sugarbag honey. They hail from near Mount Isa, way ‘off country’, well south-west of Cape York. Yet no one questions their right to be here. “We are one troupe, but many nations," says community representative Ronaldo Guivarra, in between wheezy post-performance pants.

“We are acknowledging the Stolen Generations. Laura is usually only for Cape York, but we decided to bring all the Kalkadoon kids along because of the link to Mapoon Aboriginal community: the first Aboriginal mission in Queensland. Lots of Queensland’s Indigenous people who were stolen were processed through Mapoon and taken to other missions," he continues. “So a lot of people here are from Mapoon; they intermarried and became landowners in other countries."

There’s a saying I hear more than once at Laura, which also seems to manifest in many of the dances too. There’s a few versions, but the gist goes: “Sometimes, when you go far away off country [whether forcibly or by choice], the mountains, your country, will bring you back."

Perhaps that’s why, every two years, so many travel so far to a tiny piece of earth that most Australians will never come close to. Not only to witness the collective colour and movement of the world’s oldest culture stir up the dust of their past, their present and their future. But also to interact with the owls, and things they might not exactly understand, which have found their way back, which will help the next generations move forward.

And may the dust never, ever settle on that.

Details: Laura Aboriginal Dance Festival, Cape York

Getting there: The Laura Aboriginal Dance Festival takes place at Ang-Gnarra Festival Grounds, 15 kilometres south of Laura town, 330 kilometres north of Cairns.

Playing there: A camping pass for the 2017 event was $150 (shared shower blocks).

Another way to be there: You can volunteer at Laura for free admission (transport not included). “This is a life-making experience," says Jo from Sydney. “It’s definitely worth cleaning backed-up toilets and finding lost children."

The next one: Laura is held in June every two years; the next one is in 2019.

Amenities: There are a couple of genuinely good coffee stalls and a surprisingly diverse range of food outlets serving everything from traditional dishes such as pig’s blood and rice to plenty of less-challenging standards like bacon and egg rolls.

The crowd: Over three days there were around 1000 performers, 23 communities, and 9000 spectators from as far afield as Chicago and Japan.

MORE… After Laura?

1. Tip to the trip: the classic Cape York road trip

2. Cape York the hard way: Cape York to Cairns by motorcycle – the long way