Before there was Hugh and Nicole, there was Mad Max, Priscilla and Mick Dundee. And with Australia the Country now distilled into Australia the Movie, George Dunfordcharts the history of our Big Country on the Big Screen.

Long before Hugh Jackman cracked a stockwhip over the country or Tourism Australia got Baz Luhrmann to cut their ads, the backdrops were landing starring roles in Aussiewood. Where would Mick Dundee be without somewhere to wrestle crocodiles? Or the Man from Snowy River without flint stones to send flying? And where would Priscilla and her desert queens have gone without King’s Canyon to live out the dream of a cock, in a frock, on a rock?

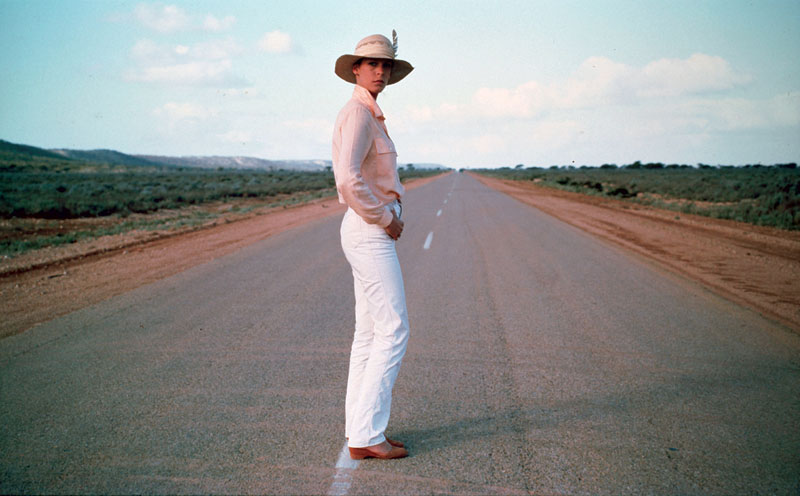

Whether it’s winsomely crying “Miranda!" or revving up an Interceptor on a desert highway, everyone’s got their own moment of classic Aussie cinema that put a place on the map or a name up in lights.

All over Australia

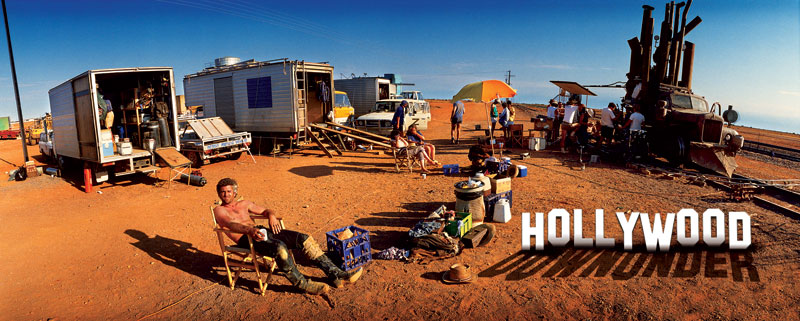

In case you missed Moulin Rouge, Baz Luhrmann likes a big canvas. While scouting locations for Australia, almost the entire landscape got a casting call – in particular the Kimberley region. Sure, he could have shot the whole shebang at Sydney’s Fox Studios and tricked in backgrounds with CGI, but that’s not how Baz paints.

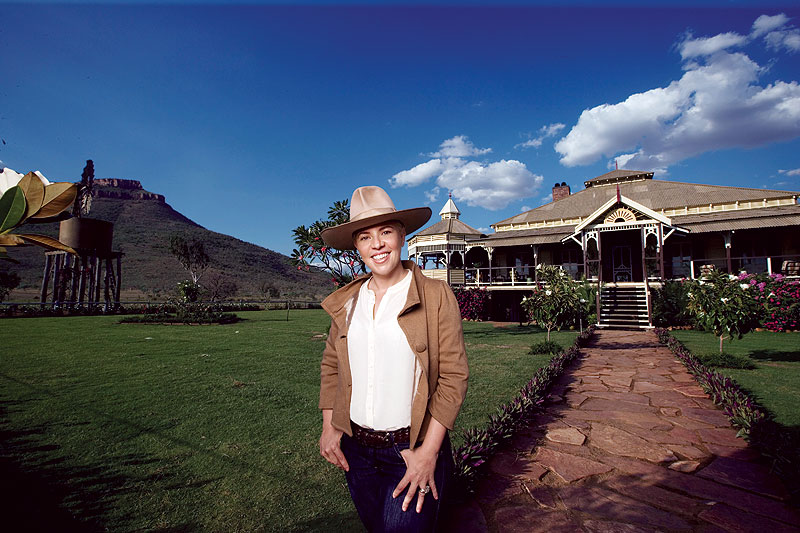

To create Faraway Downs, the mythical property Nicole Kidman’s British aristocrat Lady Sarah Ashley inherits, a massive working cattle station was built near Kununurra. The two stations and resorts now synonymous with the project are El Questro and Home Valley Station. Shooting was plagued by torrential rains and equine flu, but a small army camped out under the stars to get the perfect shots. For a crucial mustering scene, the crew had to hold back more than 1000 head of cattle until dusk when Luhrmann’s “magic time" saw the country drenched in the ideal orange-red by the retreating sun. While there’s little of the set remaining, stars left their mark at the Celebrity Tree Park – with Jackman even planting a quirky boab.

The film’s dramatic climax is set in Darwin, but as the city no longer suits the 1940s period of Luhrmann’s film they had to build somewhere “more Darwin". The tiny Queensland town of Bowen swiped the title from the NT capital with another massive set construction to take it back in time. Locals were drafted in as extras and when filming wrapped many got to see “Mr Kidman" Keith Urban play a three-hour set at the wrap party. Now the town that was famous for the Big Mango is taking on the name Bowenwood.

Sydney gets a look in as a location, with Vaucluse’s Strickland House doubling for Lady Sarah’s posh manor. Steamier sex scenes between Kidman and Jackman were shot behind closed doors on the lot at Fox Studios, and to recapture a missing scene the studio had to double as Kununurra, which meant importing tonnes of dirt of the exact deserty colour. While in town, Jackman also filmed crucial scenes from his upcoming Wolverine movie. The highlight was on Cockatoo Island where a buffed-up Jackman was seen running naked through the night for an escape scene. Although he was actually wearing a body stocking to avoid freezing, it’s a scene Sydneysiders were glad to catch a preview of.

Pubs

Silverton Hotel, NSW:

Easily the most filmed pub in Australia, this sleepy spot in Silverton has changed names 15 times to appear in everything from feature films to beer ads. You might know it from such films as Mad Max 2, Wake in Fright, A Town Like Alice and the Ozploitation schlocker Razorback. In real life the Silverton Hotel is a shy star, hiding out in a ghost town.

Owner Ines McLeod remembers when they started filming MM2. “I looked out the window and all these weird looking blokes in leather were hanging around and I wondered what we were in for," she says. “They used to come in dressed up in their outfits to have lunch in the beer garden."

The pub walls are papered with evidence of its glittering silver screen career. Amid corny jokes and a bust of Menzies (labelled Ming the Merciless) are cheeky snaps of Bryan Brown on the set of Dirty Deeds and Mel in the famous Interceptor. Nothing seems to ruffle Ines, who’s helped out on the biggest productions. “Sometimes they need a snake or want someone that can stand on their head and crack a whip," she says. “We always seem to be able to find what they want."

Walkabout Hotel, Qld:

Ever wondered where Mick Dundee (Paul Hogan) first wrestled a stuffed croc to impress a US journo and create a worldwide smash? After dodging roadtrains for 104km southeast of Cloncurry, you’ll find the small town of McKinlay and its Walkabout Creek Hotel, renamed to match the film’s boozer. It’s decorated with candid photos of Hoges mugging for the cameras, but even more of Linda Kozlowski in that thong swimsuit that had Hoges swapping wives. After Crocodile Dundee’s success, the pub sold for nearly $300,000 – an investment recouped by the sale of the popular Walkabout Creek Hotel T-shirts.

Beaches

Gallipoli Beach, SA:

On Anzac Day many Australians will remember, not a beach in Turkey, but a secluded chunk of SA’s Eyre Peninsula made famous by Peter Weir’s Gallipoli. On these expansive beaches, a young Mel faced off against blokes recruited from the footy teams of nearby Port Lincoln, drafted to play Turkish soldiers. The beach is still called Gallipoli Beach (further confusing it with its international namesake), lest we forget the great Aussie film. You can still run into extras from the Aussie war epic in the streets of Port Lincoln, but these days they’re Ute-driving millionaires, not from the box office but from tuna sales.

The Coorong, SA:

Skip the glammed-up Sydney beaches or sandy shoals of the Great Ocean Road. The heart-warming children’s film Storm Boy showed us a moody overcast beach on which a boy and his pelican, Mr Percival, played. Fingerbone Bill (David Gulpilil) watches over the two as they play in the dunes and saltpans of the Coorong National Park. The park remains a major breeding ground for waterbirds, particularly pelicans, so local Aboriginals called it Kranangk (“long neck"). While shooting the film three local long necks played the part of Mr Percival and even got the star treatment in a swimming pool out the back of Adelaide’s SA Film Corporation.

You can find the long stretches of coast just 88km drive south of Adelaide and re-live the Storm Boy’s chase after pelicans on the beach. You mightn’t find Fingerbone Bill, but Aboriginals still offer tours of the area, like the mob at Camp Coorong (www.ngarrindjeri.com) and the Coorong Wilderness Lodge (www.australiantraveller.com/coorong), who do guided trips through the Coorong pointing out bush tucker and telling yarns.

Outback

Coober Pedy, SA:

When Ava Gardner was making On the Beach in Melbourne, she cattily wrote the city off as “a great place to make a film about the end of the world." She obviously hadn’t seen Coober Pedy, which has been given the apocalyptic guernsey in films like Mad Max 3: Beyond Thunderdome. The Breakaways, freakish outcrops of multi-hued rock, hogged the screen in MM3, but were equally popular as other planets in sci-fi flicks like Red Planet and Pitch Black. The area was once an inland sea that dried up, leaving sediment levels coloured from rich ochre to stark white.

The spot certainly left its mark on Hollywood hunk Vin Diesel, who for his role in Pitch Black wore contacts so thick he called them hubcaps. The intense heat caused an eyewear malfunction that virtually glued the hubcaps into his eye sockets and an optometrist had to be flown in from Adelaide so filming could continue.

Pitch Black also left its mark on the town, with several props still around, including the spacecraft left outside a hostel (in case of backpacking Martians). It’s a compulsory cliché if you’re visiting to take a sticky beak into an underground home – Tina Turner certainly did while filming MM3. A pair of her undies are nailed to the roof among a sea of other fans’ knickers in Crocodile Harry’s infamous subterranean abode. Harry himself could be the subject of a film as he reckons he’s a Latvian baron who became a crocodile shooter, a possible inspiration for Paul Hogan’s Mick Dundee.

The Pilbara, WA:

In Japanese Story, filmmaker Sue Brooks always believed there were three main characters: the geologist, the Japanese businessman and the Pilbara. While the geologist (Toni Collete) and the Japanese businessman (Gotaro Tsunashima) gradually fall for each other, the surrounding desert forms the lonely third part of the love triangle, captured in bleak long shots. Just getting access to the film locations meant long negotiations with traditional landowners, and then there was the red dust that seemed hell-bent on clogging all the equipment. Without trespassing, the best chance to see the Pilbara is in Karijini National Park, in particular, Kalamina Falls, which could have been the setting for the movie’s tragic turning point.

McDonald Ranges, WA:

Never heard of The Overlanders? Baz Luhrmann definitely has, as Australia shares its crucial cattle-driving plot with this 1946 classic. If you catch it now you can compare our Hugh with the legendary Chips Rafferty’s performance as a toughened drover. But the Outback Oscar should have gone to the rugged country, which positively leaps to life even in black and white. The film follows the Murranji Track, a stretch of almost 2500km from WA to Qld taking in some of Australia’s rawest desert and lushest bush. Most of the film was shot in the McDonald Ranges that’s been a must-see since this first “Australian western" hit the cinemas.

High country

Merrijig, VIC:

When Australians think of stockmen, the icon is still a bloke who rounded up the colt from Old Regret while winning Sigrid Thornton’s heart. When it came time to make the movie of Banjo Patterson’s poem, the Snowy Mountains were re-located to the Victorian High Country. The twilight scenes of Jessica (Sigrid Thornton) and Jim (Tom Burlinson) romancing in silhouette were actually not filmed around Kosciuszko way, but not far from the Victorian town of Merrijig.

The snow gums and ravines that made for white-knuckle horse wrangling in The Man From Snowy River are easily accessible today, with some of the set left behind for tourists and the possibility of another sequel. On Mt Stirling, the shell of a cottage custom-built for the film called Craig’s Hut overlooked the valley – until it was burned to the ground in bushfires in 2006/07. It has now been restored to its former glory, and if you listen out over the valley you might hear the rumble of hooves as the Man canters home . . . or is that just a 4WD tour?

Hanging Rock, VIC:

When Peter Weir wrapped on his kooky The Cars That Ate Paris in the tiny NSW town of Sofala, he wanted to make the Australian bush as sinister as the small town besieged by cars in his first feature. He found Joan Lindsay’s novel Picnic at Hanging Rock and got a spine-tingling location into the bargain. Set on Valentine’s Day 1901, the film traces the disappearance of three schoolgirls, including teen queen Miranda, during an excursion that veers towards the occult.

More than just dreamy shots of the rock or an eerie warning for bush-wandering kids of the ’70s, the film took off overseas, scoring best cinematography at the BAFTAs. Amid rumours that filming was plagued by supernatural quirks like watches stopping (as they did in the film right before the girls disappeared), people flocked to the Macedon Ranges to forlornly cry “Miranda!" as they climbed Australia’s second most famous rock. The film is still screened at Hanging Rock every Valentine’s Day and, despite its spooky reputation, the movie monolith remains a popular spot for picnickers.

Big cities

Sydney:

Although heralded as Australia’s own Gotham City, Sydney is yet to play host to any of the Batman films. But it has formed the backdrop to well over 200 others, ranging from four-hour Bollywood epics (the last half of the inexplicable 2001 Hindi love story Dil Chahta Hai features some of the most stunning and sweeping views of Sydney ever committed to the silver screen) to Star Wars I and II, Two Hands (Bondi Beach, China Town and Kings Cross) and the famous Matrix trilogy. Neo and his pals stalked in front of a variety of CBD landmarks, as did Brandon Routh as the man of steel in Superman Returns, choosing to hang out mostly near Wynyard Station (aka the offices of The Daily Planet).

When Tom Cruise came to Sydney for Mission Impossible II, he took audiences on a whirlwind tour, from The Rocks to Ashton Park near Taronga Zoo, La Perouse, Elizabeth Bay, Governor Phillip Tower, Royal Randwick – even Broken Hill. Of endless entertainment to viewers of this film are the collection of mostly geographical errors it contains.

Like the tracking device that places our heroine in Sydney, backed by a laptop map with a blinking marker midway between Cairns and Darwin. Or our heroine being dropped off by car in the middle of the pedestrian-only Darling Harbour. Or the IMF team preparing to storm Governor Phillip (aka Biocyte) Tower with a street map of London. But hey! It’s the movies!

Melbourne:

Widely recognised as the world’s first feature length film, many of the scenes from The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906) were shot in Melbourne suburbs, including St Kilda, Eltham and Mitcham. Since then, more than ten feature films have been made about Australia’s most infamous bushranger – the most recent being Ned Kelly (2003), starring the recently departed Heath Ledger, which was largely shot in Ballarat. (At least it was shot in Victoria; the 1970 Ned Kelly starring Mick Jagger was controversially filmed in NSW, drawing protest from living Kelly descendants and many others.)

Melbourne has hosted a swathe of other big and small name movies over the years, including: Ghost Rider with Nicolas Cage (Docklands, Flinders St Station, even Telstra Dome); the incomparable Kenny, Australia’s most famous waste management artisan (Chapel St, Flemington raceway and other spots); Eric Bana as the compelling Chopper (Pentridge Prison); The Castle, which elevated outlying Bonnie Doon to iconic status; the original Mad Max (Melbourne Uni’s car park as Mel’s HQ); Rusty Crowe as a head-butting skinhead in Romper Stomper (Footscray and Richmond); and not forgetting Road Games (1981), a frankly appalling movie starring Jamie Lee Curtis, which was filmed in Diggers Rest near Melbourne airport, as well as locations ranging from Port Melbourne to Eucla to the Great Australian Bite.

Its tagline – “The truck driver plays games. The hitchhiker plays games. And the killer is playing the deadliest game of all! – should tell you everything you need to know about that classic piece of Ozploitation cinema.