From Country to coast, Arnhem Land offers an invitation to connect with the spirit of an ancient landscape.

I’ve been told more than once, by people who know a lot more about it than me, that if you just listen, Country will speak to you. Floating on this large tinnie with the engine cut on a ‘side street’ of the Arafura Swamp near Murwangi, I can finally hear it – even if I don’t yet understand the language.

It’s too hot for cicadas, but the waterbirds of Arafura are providing the soundtrack to this experience. The mad cackle of blue-winged kookaburras. The high-pitched calls of plumed whistling ducks. The majestic cries of various kite species as they circle overhead.

And the resonant honks of magpie geese, totems of the local Ganalbingu People and allegedly very good walle (eating), although you’ll need to go through the correct ceremonies to find out. All the while, wind has become a telephone to the elements, rustling through the gum trees and Arafura palms.

There aren’t many crocodiles right now – recent flooding has made their territory a whole lot larger than the usual 700 square kilometres of freshwater ecosystem they have to wallow around in. But they’re still here to join in the cacophony of life.

In fact, our first crocodile makes itself known just as our guides – Ganalbingu man, Graham Gunurri and adopted Indigenous man, Lachlin Dean – stop at a significant landmark that relates to a local songline. We only get the topline version – the rest is only shared during ceremony – but what is clear is that a crocodile spirit was trapped under the water below us for stealing fire during the Dreamtime. No sooner has this been shared than the thrash of a tail and the whip of a pointed, scaly nose indicates that a free-roaming crocodile just caught itself a juicy fish for lunch.

Arnhem Land with Outback Spirit

This is only day four of Outback Spirit’s 13-day Arnhem Land Wetlands & Wildlife wilderness adventure from Cairns to Darwin. Starting with a flight from Cairns, in Tropical North Queensland, into the Northern Territory’s Gove Peninsula, spending the first few days exploring Nhulunbuy and Yirrkala.

Before we’d even touched down, it was immediately clear that Arnhem Land stands apart from the rest of Australia. Looking out my window, I was struck by how untamed the landscape is. In most parts of this country, you only get glimpses of this sort of ‘wild’ before farmland or buildings tear it apart. But not here.

“Just wait until you see the golden dirt," my seatmate, Lisa, leaned over to tell me. “It’s so red." Lisa is a local, returning from a quick trip to Sydney – a very long way for a doctor’s appointment. But she was relieved to be returning home. “I just want a peaceful life. It’s a peaceful life here," she shared.

Outside my window, the dense, dark-green blanket spread out over the land continued untouched until we flew a little lower, when that red dirt Lisa prepared me for breaks through. In the last of the day’s light, the winding roads glow like the veins and arteries of the Earth.

“This has to be the most beautiful airport I’ve ever seen," I exclaimed. Lisa just smiled, satisfied.

Welcome to Gove Peninsula

The next day, our group of 15 heads out to Wirrwawuy Beach where we receive a Welcome to Country by the Traditional Custodians of the land, the Galpu clan of the Miwatj (north-east Arnhem Land), part of Yolŋu Country. The joy we are privy to is infectious. Following the lead vocals of Lita Lita Gurruwiwi (born performer and, I suspect from his endless jokes, larrikin), we trace the songline of a spiritual man searching the land for food and water. It’s a family affair. Clan leaders play clapping sticks and yidaki (the Yolŋu word for didgeridoo). Three-year-old children pay close attention to the hands, feet and cries of the adults around them. They join in for the promise of a lolly and then abandon the show in favour of their own games.

A soft breeze rustles the leaves of the tamarind trees we sit under, bringing with it the gentle scent of ocean, just metres away from our shady patch. Excitement ripples through our group and the performers alike when a dolphin and her baby are spotted playing in small waves, connecting us further to the natural world around us. This is about sharing.

To close the Welcome to Country, jilka leaves are used to create a cleansing smoke. This same smoke is used to cleanse the belongings of the deceased, and then the loved ones of their grief. It’s also used to help connect new generations to Country. Today, it is used to make us safe on our travels through Arnhem Land.

Spotting wildlife at Arafura Swamp

It’s a safety I’ll be especially thankful for on day four, sleeping at Outback Spirit’s exclusive Murwangi Safari Camp on the banks of the Arafura Swamp. While earlier in the day I heard Country, the message it’s sharing becomes loud and clear in the night.

While curled up in my comfortable safari tent – reading a book by lamplight with the zips tightly closed against the mosquito population – the nightly soundtrack of cicadas and birdcalls is suddenly, and violently, split in two.

A large splash, a low, primordial growl, one desperate squawk and then silence. The most eerie silence I’ve ever heard. The birds, geckos and cicadas don’t start up again for a good five minutes. I’ll never know for sure, but I feel confident the world stopped to honour the lost. I’ve seen a lot of crocodiles before, even in the wild. But something about this aural encounter feels more visceral than anything I’ve ever laid eyes on.

I’ve spent plenty of time on different lands around the world, but I’ve never witnessed the breathtaking busyness of such a remote one before. And this is only our second stop.

Dropping a line at Maningrida

The next day, we head to Barramundi Lodge, another safari-tented stop just outside the small community of Maningrida. Typically, we’d be driving for hours along red-dirt roads, but flooding as a result of record-breaking rain has rendered many of them closed. None of us complain as our 12-passenger aerial caravan flies us overhead instead. Showing off more of this beautiful country and keeping us oriented.

Here, swamp banks are swapped for the privacy of stringybark and woollybutt gum trees that surround each tent. The main dining cabin boasts sweeping views of the plain below, transformed each evening under the vibrant oranges and reds of sunset.

The name is no mistake. Every year, Barramundi Lodge attracts guests hoping to catch themselves a juicy barra. A metre-long club plaque hangs proudly near the kitchen. And, while some members of our group do have luck with their fishing rods out on the nearby Liverpool and Tomkinson rivers, it’s again the wildlife that captures my attention.

Mud skippers turning muddy mangrove banks of the mid-tide to silver as they scuttle around. Egrets stretching their long legs as they wade along the edges of the water. A white-bellied sea eagle circling overhead. And of course, crocodiles. Dozens lining the banks, soaking up the morning sun, proving completely unbothered by our existence, while tiny waving crabs dance all around them. Pandanus and towering paperbark trees indicate where the salty mangrove water stops and freshwater begins.

Keeping culture going

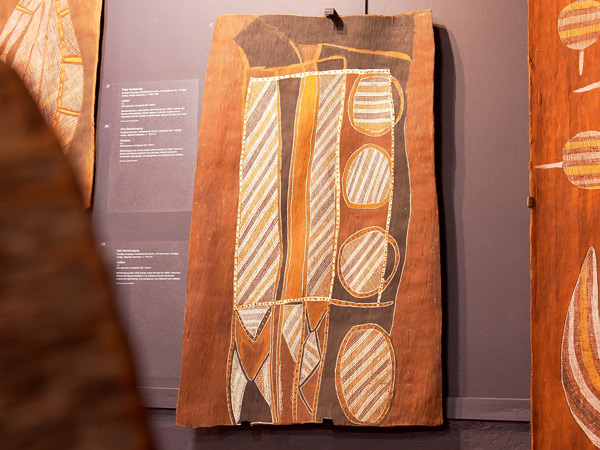

With all fishermen satisfied, we head back to shore and over to Maningrida Arts & Culture centre – the oldest and largest of its kind in the Northern Territory, with all profits going back to the artists – and the Djómi Museum.

Doreen Jinggarrabarra is our guide to both, a leading fibre artist whose work has been shown in galleries around the world. Doreen shares with us the basics of her art form, weaving pandanus leaves into magic before our eyes. Although a full dilly bag would take two to three weeks to complete, the large installations she exhibits take even longer.

Despite her huge success as an artist, it’s not until Doreen has finished walking us around Djómi that she allows a modest sense of pride to enter her tone. But it’s not for herself.

“We don’t forget our culture," she tells us. “We teach our kids. We keep it going."

And that’s what the museum is about. Keeping it going, even outside the community. Doreen walks us around artefacts and artworks, meticulously explaining the materials and use of each one. Or, at least, those of the Eastern clans to which she belongs. For the items collected from further away, Doreen sits down. They’re not her stories to tell.

We learned back at Buku-Larrŋggay Mulka Centre in Gove Peninsula that this is essential to local culture. Songlines are held within every artwork and every artefact. The Yolŋu don’t deal in numbers, we were told. But it’s safe to say that tens of thousands of years of knowledge and history are written into these artworks. Sharing a songline that doesn’t belong to you is a huge offence, the traditional punishment being death.

Exploring the rock art of Mt Borradaile

It’s an education we take with us into our next stop, Mt Borradaile, famed for being home to the largest outdoor rock art gallery in the world, some of which dates back as far as 55,000 years. It’s impossible to count the number of artworks across the 700-square-kilometre area where the remote safari lodge is nestled against the Arnhem Land escarpment.

Escarpment country is different again. Gum trees still abound and water isn’t far away, but we find ourselves in the middle of dusty, rocky land. Deep red and brown tones take over here.

A buffalo hunter turned environmentalist who opened eco lodge Davidson’s Arnhemland Safaris here, Max Davidson was granted permission to use the land by the Amurdak People who own it, and his friend Charlie Mangulda in particular – the last man who can say he belongs to this Country. After stumbling on one of the largest known depictions of the Rainbow Serpent in Australia, they decided to share the art instead.

While modern artworks are more detailed, showing everything from mythical figures and local animals to guns and boats, it’s the oldest, simplest displays that really get under my skin. Grass strikings and handprints are believed to serve as the original mark on Country. I can’t help but wonder who that person was, with a handprint so like mine, leaving signs of life tens of thousands of years ago.

The afternoon is spent out on Coopers Creek. Once again, I’m struck by the beauty of Arnhem Land’s waterways. The way they teem with life, making them at once the busiest places I’ve ever seen, yet somehow also the calmest. Wild rice lines the banks, where hundreds of magpie geese fill the air with their honks. And then with their bodies as they occasionally take flight, creating a spotty blanket against the clear sky.

Nearby, a whistling kite swoops a dead fish floating in the water. He eventually gives up and flies away, possibly in embarrassment. Crocodiles tease us from along the lily pads lining the edge of the creek, dipping below the surface when our boat gets too close.

Meanwhile, the sculptured cliff faces of Mt Borradaile itself change colours as the sun moves lower in the sky. And our little tour group, in the middle of it all, is the only sign of human interference.

Ending in luxury at Seven Spirit Bay

It’s almost a shock when we find ourselves at Seven Spirit Bay on the Cobourg Peninsula the next afternoon. While the earthy tones are not entirely gone, they are mixed with a white ochre and the vivid green of native plants recently treated to rainfall.

Our lodge sits above the pristine sands and calm waters of the bay, cruelly enticing guests to dive right in even while crocodiles and sharks make that impossible. Like one of our guides will later say: “I don’t like going in the crocodile’s bathtub."

Crossing the Arafura Sea at the top of Australia, we explore Victoria Settlement, the third, ill-fated attempt at British settlement in these parts and the motivation for many in my group to join this tour in the first place. Remnants of buildings and graves remain crumbling as plants slowly reclaim their territory.

We head back onto the water the next day to fish. The unsheltered water is rough enough to have us bouncing like we’re on a roller coaster. Wide, open ocean is replaced by striking, corrugated cliffs, eroded over the years by rainfall and leaving trees desperately clinging to red and white ochre with their exposed roots. We find a place to drop a line in.

Upon return to the lodge, we notice lemon sharks circling the pier, hoping to feast on the remains of our freshly caught fish as it’s prepared for tonight’s dinner. This last stop of our Arnhem Land journey feels like another world entirely. One where the gentle lapping of the ocean lulls us to sleep each night, and elevated accommodation offers more space than we’ve had in two weeks.

Our 13-day journey will end tomorrow with a sunset cruise along Darwin’s famous Mindil Beach, but the emotion of leaving Arnhem Land hits me tonight. This isn’t a journey all Australians will take in their lifetime. But it is one that will never be forgotten by those who do.

A traveller’s checklist

Getting there

Fly direct to Cairns Airport from all major cities with Virgin, Jetstar and Qantas. Outback Spirit and Airnorth will take it from there.

Playing there

Outback Spirit is the only tour operator to take guests across the entire top of Arnhem Land (from east to west). Join the Arnhem Land Wetlands & Wildlife tour between May and September, from $11,795pp twin share. All accommodation, transportation, permits, food and drinks included.