A landmark new cultural beacon and the rich threads of the region’s defining stories – shaped by its river and wetlands, and a long legacy of activists and entrepreneurs – are bringing the undiscovered depth of Shepparton and the Goulburn Valley to light for visitors.

The view from Shepparton Art Museum’s fourth-floor terrace frames the natural landscape it faces: water, forest, a big open sky. It offers an unfamiliar perspective for a low-rise city that lies spirit-level flat, eliciting an emotional response in guest curator Ian Wong. From this sky-scraping spot on the shores of Victoria Park Lake, its wetlands blurring into the Goulburn River, we can gaze out towards neighbouring Mooroopna, where, on the riverbank in 1877, his ancestor Ah Wong established the area’s first market garden, and to the river red gums of the Barmah Forest beyond. In a place famous for its industry, the view anchors us back to Yorta Yorta Country. And in doing so articulates something of the essence of this major new cultural destination that rises small and tall out of the floodplain, two hours north of Melbourne in Victoria’s Goulburn Valley.

“We’re elevated and presented with the forest," says Wong, an industrial designer by trade, of this view that makes him look at his hometown differently. “It is not pointing towards the rooftops: the architects have controlled our vista and brought to us this vision of the beauty of the natural environment."

The design story

Designed by internationally acclaimed Denton Corker Marshall, the $50 million new SAM – as it’s dubbed – opened its doors in November 2021: a place-making landmark on the road into town that’s destined to put Shepparton on the map. At a time of regional renewal and growth across the country, its significant social and economic impact will no doubt be felt in the years to come, and we only need to look at the Frank Gehry-designed Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao or Hobart’s avant-garde Mona to see the effect that mould-breaking destinations like this can have on a place.

A sculptural, cubic form composed of strong angles and betraying little of the life held within, the building is bold and striking from the outside. Four thin plates that make up its facade – L-shaped to reference the overhang of the archetypal Australian verandah – appear suspended in space. Its different metallic finishes also speak to its surrounds, including an ochre-red corten steel that reflects the pigment of the natural environment, and signal the four functions this valuable community asset serves at street level, with entrances to Aboriginal art centre Kaiela Arts; the Greater Shepparton Visitor Centre; SAM Cafe via an ‘Art Hill’ that folds the museum into the landscape; and the gallery space itself via the forecourt where a major new commission, House of Discards, by leading contemporary artist Tony Albert stands both strong and seemingly precarious: a stack of oversized playing cards also rendered in steel.

What to expect

Inside, natural light pools into a gallery space split across five levels whose enveloping warmth and sense of welcome contrasts the toughness of its exterior and belies its newness: no stark white cube here. A wide internal staircase creates a feeling of openness as it twists upwards past a cathedral-scale window, connecting us time and again to the museum’s unique context of water and wetlands.

“That’s about giving those slats of views rather than revealing the whole thing, and framing the landscape through those little moments of light and clarity," says SAM’s outgoing director Rebecca Coates, as we wind our way from top to bottom. Coates led SAM’s journey here from its former home in the CBD over six transformational years.

“In a way it could be anywhere in the world, but in a way it couldn’t," she observes: a world-class art museum engaged with global ideas, but inherently linked to the land it’s placed on and to the local community it’s part of.

I find art layered throughout the building that tells the many stories of Shepparton and surrounds in such a way that could absorb me for days. Stories like that of the 4.6-billion-year-old meteorite that rained down on the nearby riverbank town of Murchison in 1969. One of the rarest and most primitive meteorites to ever land on Earth, it is still studied by scientists all around the world today and offers insights into the origins of the solar system. You can visit Murchison Heritage Centre to see a chunk in person, while here at SAM it is referenced in James Geurts’ site-specific neon installation, Trajectories: Orbiting Bodies Meet (until 13 November), crash landed on the fourth-floor terrace.

Hundreds of higgledy-piggledy, patterned ceramic medallions glazed in the verdant shades of a garden in bloom and assembled together in a large sprawling sphere form a centrepiece of the exhibition Flow: Stories of River, Earth and Sky in the SAM Collection (until 25 September). Artist Glenn Barkley’s under the dump a garden – roundel for a garden garniture reflects not only SAM’s Australian ceramics collection – one of the museum’s two core focuses and the most significant in regional Australia – but the Australian Botanic Gardens Shepparton, which I visit the next morning. Located on the fringe of town and demonstrating the resourcefulness of the community, it’s hard to believe this peaceful spot regenerated with a patchwork of native plants was once the local tip.

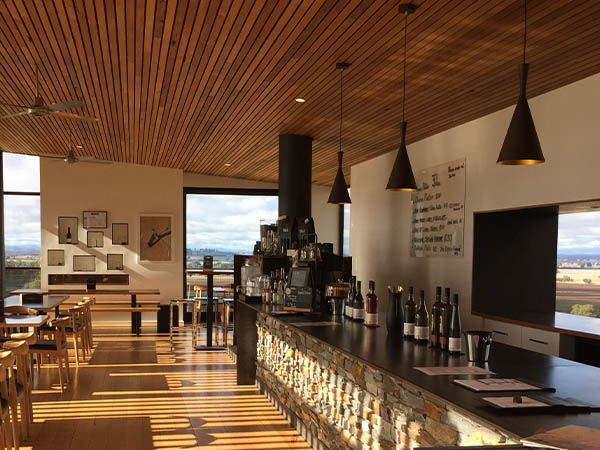

The stories flow into transitory spaces, too. Installed at the interior entrance to the SAM cafe (timber-toned, cool and animated when I visit for lunch and Melbourne-grade coffee, and already a favourite haunt for locals), Wong’s exhibition Everyday Australian Design (until 2 May) celebrates Australian manufacturing, daily life and culture. Drawn from his personal collection and presented in compelling pops of block colour, objects such as a cherry-red Hula Hoop sourced from a local primary school spark resonance all round.

I linger on the staircase to take in Congolese-Australian painter Pierre Mukeba’s striking portrait, Determination, 2017, and Iranian-born Australian artist Hossein Valamanesh’s spare and stirring Untitled, 2008 – a ladder ascending the atrium as if infinitely. These works purposefully reflect the people and experiences of our place and times, and speak to the fabric of Shepparton’s population. Proudly diverse and multicultural, the regional city has long been home to successive generations of economic and refugee migrants, beginning with the first wave from Southern Europe following the First World War.

Indigenous influence

It is SAM’s integration of First Nations art that perhaps sings the loudest – it currently holds 319 Indigenous works (making up eight per cent of the collection), including the largest holding of works by the extended Namatjira family in any state or regional gallery, and the donated Carrillo and Ziyin Gantner Indigenous Art collection, which is valued at more than $3 million. The new building was established as a place to embed an Indigenous understanding and inclusiveness from the outset, says Coates, beginning not least with the furniture couched invitingly throughout the museum. With fabric featuring paintings made with charcoal pigment from a campfire ceremony, they’re the result of a collaboration between Melbourne design studio Spacecraft and artists from Kaiela Arts that weaves the local Aboriginal community into the DNA of the building.

SAM also holds the most significant collection of south-east Australian Aboriginal art in the country. Australia’s south-east has often been overlooked in conversations about First Nations art and now, at a time of greater awareness of and renewed interest in the work of this vast corner, SAM aims to be a catalyst for this change. The centrepiece of its launch program signals this intent. The first significant showing of works by acclaimed Yorta Yorta artist Lin Onus on Country, Lin Onus: The Land Within (until 13 March) is a captivating journey through a career that defied categorisation. Developed working closely with Onus’s son, Tiriki Onus, and supported by a Custodial Reference Group, the exhibition brings together work spanning painting, prints and sculpture from the 1970s until the artist’s death in 1996; his magnificent renderings of Barmah Forest, his ancestral home and final resting place, are an affecting focal point. His works bold and often irreverent, blending traditional and contemporary references, Onus explored the reverberating impact of colonisation and the struggle for Indigenous rights, and reflected an unwavering spirit and strength that courses through the region.

The legacy of political and social activism and change runs deep within Shepparton’s Aboriginal community and it doesn’t take long for this to reveal itself as I wander the streets of the CBD: the huge, chiaroscuro brushstrokes of Matt Adnate are unmistakable. The Melbourne-based artist paints bold and expressive murals on the sides of buildings around the world that draw attention to Indigenous issues and, here in Shepparton, they celebrate the rich local Aboriginal culture and history through portrayals of key figures. When complete, the Aboriginal Street Art Project, known as Dana Djirrungana Dunguludja Yenbena-l, meaning Proud, Strong, Aboriginal People in Yorta Yorta language, will connect SAM with the CBD. (It also forms part of a larger public art trail that winds through Greater Shepparton, including nomadic silos in the rolling hills of Dookie, the new mural of General Sir John Monash on a historic water tower in Tatura, and the region’s famous Moooving Art cows.) Among those rendered in primary-hued spray paint is the extraordinary William Cooper (1860–1941), a political activist and community leader who campaigned for Aboriginal rights and, following Kristallnacht in 1938, is also recognised for protesting against the Nazi Government for its persecution of Jewish people.

Cooper was instrumental in the first-ever mass strike of Aboriginal people when in 1939 around 200 Yorta Yorta people staged a Walk Off from Cummeragunja Station across the border. Many settled in an area known as The Flats on the banks of Kaiela (the Goulburn River) in Mooroopna and created their own community that strived and thrived for almost 20 years. Interpretative signage lines the Mooroopna Aboriginal History Walk – a tranquil 4.3-kilometre waterside stroll flanked by native grasses and river red gums – to offer insight and remembrance into the everyday lives of those who lived here.

The Goulburn Valley

The Goulburn Valley is full of stories of entrepreneurship, vision and resilience like this that have been something of a well-kept secret until now. “SAM is the embodiment of that undercurrent – it’s that sense of pride and sense of self," considers local tourism consultant and operator Carrie Donaldson. “Shepparton has been a community and a destination that has struggled with its own identity and being able to express itself in a way that resonates with everyone because it is so diverse." But the area is increasingly finding greater expression through these different threads of curation and storytelling, and a renaissance of bold architecture including new civic buildings.

“It’s really terrific to see that now being reflected on the landscape," says Donaldson. “There are a lot more new businesses open and there’s that sense of endeavour being reignited." Through Town & Country Stays, available to book via Airbnb, she keys into these threads: the Art Deco Miss Boulevard, a stone’s throw from the river in Shepparton; the Mid Century Modern-style Art House, walking distance from SAM; and the Storekeeper’s House, 20 minutes down the road in Tatura, which brings to life the history of a 1905 heritage home in luxurious and character-filled style. Across the quiet main street from here (with its small, vibrant community, grand architecture and requisite award-winning bakery, Tatura is the country town idyll) is a small and superb volunteer-run museum that sheds light on the region’s eye-opening history of Second World War internment and POW camps, as well as the irrigation history that has been central to its development and prosperity over the last 150 years.

The Goulburn Valley is known as a food bowl and its boundaries are sketched by the river and irrigation footprint, stretching from Seymour, just 90 minutes from Melbourne, to Echuca on the Murray River. It’s where shimmering waterways give way to flat plains of dairy pasture and orchards drip with stone fruit, cherries, apples, pears, grapes, olives and tomatoes. Its dairy and agriculture industries are inextricably linked to its rich transport heritage, as Shepparton’s newly renovated Museum of Vehicle Evolution (MOVE) reveals. Here, following a multi-million-dollar renovation, almost 10,000 square metres of exhibition space house an ever-unfurling suite of collections that each tell their own social history: from classic, vintage and veteran cars to bicycles and motorbikes, to clothing, accessories, furniture and radios. There’s even a self-contained Furphy museum that showcases the company’s local roots and iconic old water carts that coined their own word. In the mightily impressive truck section – all proud, gleaming steel – curator Jade Burley connects the dots between the humble beginnings of local orchardists and the massive transport hub the region is today. “In a lot of cases it’s the story of first-generation immigrants that have come dirt poor with nothing and have built empires," he says. “The opportunity was here and they worked hard."

The hidden wine scene

And while the area has been busy being industrious, it has perhaps flown under the radar that the Goulburn Valley is one of the oldest wine regions in the country, with some of the oldest shiraz vines in the world. A warm climate and waterways for days make for wines that are rich, complex and well-balanced. Cast a line out from Shepparton in any direction to find unassuming family-owned cellar doors in picturesque pockets that capture the essence of the area – from Tallis Wine, which draws from the rich red volcanic soils of Dookie’s sloping hills to Longleat Wines in Murchison, with its riverside vineyard and handmade cheese. This is a place made for country drives and impromptu pit stops at unpretentious farm gates for fresh fruit and flowers.

It’s the kind of place where Mitchelton executive chef Dan Hawkins will trade a few bacon and egg rolls with a “chap down the road" in exchange for bags of cherries plucked straight from his trees. A place that doesn’t immediately reveal itself to you but rewards exploration. Right now the Goulburn Valley doesn’t have the same name recognition as other Victorian wine destinations such as the Yarra Valley or neighbouring Rutherglen, but the narrative is shifting. “There are a lot of great wineries and regional food destinations in the Goulburn Valley and it’s the food bowl of Victoria," says Hawkins, “so it seems logical that it’s the next place to be really recognised as a destination."

I wind south for 40 minutes, loosely tracing the Goulburn River, to find Mitchelton, just outside Nagambie – an attractive lakeside weekend destination in itself with a growing roster of cool spots to eat and drink. Located at a bend in the river, Mitchelton has a wetlands climate which, along with neighbouring carbon-neutral Tahbilk Winery, creates its own sub-region to produce soft and mineral-rich French Rhône styles. It’s a showpiece of the area with its monochrome tower first designed by modernist architect Robin Boyd rising out of the flat terrain and sleek hotel in serene surrounds whose balconies come with a babbling brook soundtrack. But the most astonishing discovery I make is underground. Here in the cellars where you’d expect to find wine barrels is Australia’s largest commercial Aboriginal art gallery. Helmed by art dealer and curator Adam Knight, whose career was shaped by his relationship with mentor and mate Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, it represents some of the most important artists working today including Tjapaltjarri’s daughter Gabriella Possum Nungurrayi; their vast canvases find an optimum home on the walls of this cavernous space.

Dinner is served at The Muse restaurant, which blends elegance with country warmth. From Murray cod caught a stone’s throw from here to watercress foraged from the river or wild blackberries from its bank, everything served here tells its own tale and is distinctly of its place. “We try to connect, whether it’s back to the land or the river or the winery," Hawkins says. At sunset in peak cherry season, when the sun stays high until late into the evening, I gaze out over the water as I eat – the sun casting slats of light onto those river red gums. The landscape framed, again. “There’s always got to be a connection."

A traveller’s checklist

Getting there

Shepparton is just over two hours’ drive north of Melbourne; Nagambie is 90 minutes north.

Eating there

The Teller Collective is one of Shepparton’s stand-out dining options with an inventive menu and local wines located in the city’s CBD. SAM Cafe is one of the best spots in Shepparton for coffee and lunch, with a generous side of art. Right on the river, Mitchelton’s on-site restaurant The Muse serves hearty but elegant food inspired by the landscape.

Pitch up for a gin flight, wood-fired pizzas and the best lake views in town at Nagambie Brewery and Distillery. Don’t miss the Italian-inspired fare and taste of local wines at Eighteen Sixty , a cool and intimate little spot in Nagambie. At the southern end of the Goulburn Valley, The Trawool Estate boasts drinking, dining and boutique accommodation in a landmark historic building.

Staying there

Overlooking Victoria Park Lake, Parklake Shepparton has comfortable rooms a few minutes’ walk from SAM.

Book The Storekeeper’s House in Tatura, or one of Town & Country Stays’ other self-contained, boutique accommodations in Shepparton, to tap into their unique sense of place.

Designed by architecture and interior design practice Hecker Guthrie, Mitchelton HOTEL’s 58 rooms are sleek, stylish and sympathetic to their surrounds. Or check into an on-site Airstream set between the river and vineyards.

Playing there

Shepparton Art Museum is open daily from 10am–4pm. Visit the Greater Shepparton Tourism Information Centre , located on the ground floor, for more information on what to do when you’re there.