Discover everything Queensland has to offer with our ultimate travel guide of things to see and do in Queensland. Relax on beautiful beaches, be inspired by world-heritage listed rainforests or escape to an island paradise.

Explore stunning destinations in South East Queensland such as the Gold Coast, Noosa and the Sunshine Coast or head to the tropical climates of the Daintree Rainforest, Whitsunday Islands and the Tropical North.

Queensland is a great holiday destination for family beach holidays, romantic getaways on tropical islands or road tripping to the outback; Queensland has it all.

There are plenty of things to do in Queensland and a visit to the Great Barrier Reef should be on everyone’s bucket list. Explore the Whitsunday Islands and bring a sense of adventure with sailing, ocean rafting and skydiving available to tempt thrill seekers. Families will love a day out at the Queensland theme parks for fun in the sun on the Gold Coast.

There are plenty of opportunities for snorkelling and sailing in Queensland, with The Whitsundays a popular spot for beginners and advanced skill levels alike. Try sailing the Whitsundays in a catamaran for the joy and freedom of sailing unassisted through the most beautiful waterways in the world.

Just an hour from Brisbane, swim in the crystal clear waters of Moreton Island where you can snorkel among the corroded hulls of 15 sunken ships, teaming with reef fish as well as turtles, dolphins and stingrays and coral outcrops.

If it’s adventure you seek, Queensland offers plenty of adrenaline pumping action, from diving with sharks at Osprey Reef, jungle surfing at Cape Tribulation to skydiving in picturesque locations across the state including the Gold Coast, Cairns, Fraser Island and the Whitsundays.

Relax; you’re on island time. Take some serious R&R and chill out at one of Queensland’s island destinations. Hamilton Island is the ideal island getaway, whether you splurge on a stay at qualia or stay at one of the more affordable holiday houses or hotels on the island you’ll find plenty of things to do on Hamilton Island or simply enjoy relaxing and doing nothing at all.

Cheers fun-fuelled indulgence with your people at the best places to bottomless brunch in Brisbane. At the liveliest spots to bot...

A culinary renaissance is in full swing as the best restaurants in Brisbane prove they’re simply to dine for. Australia’s din...

Get a taste of the Sunshine Coast’s freshest seafood and inventive produce-driven dishes at our favourite Mooloolaba restaurants...

Peel yourself away from that powdery white sand to experience all the heavenly things to do in Mooloolaba. The sweeping curvature...

Cairns is open for business and still one of the most epic destinations to explore in the country. The sun is shining, the cockta...

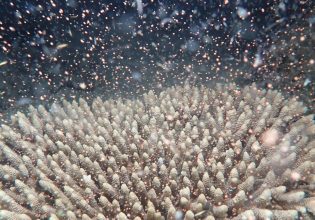

If one of the world’s most important ecosystems fails, this clever insurance policy may prove to be its saving grace; take a loo...

Set sail with this incredible sale from Royal Caribbean around Australia and over the seas. Back to work blues setting in? It's n...

Australia’s vast land can prove difficult to explore in a timely manner with a mere set of wheels, so why not take to the skies?...

Hit Australian children’s TV show Bluey is about to come to life in Brisbane. You’d be hard-pressed to find a child in Austra...

Queensland’s Scenic Rim is a gateway to ancient Gondwana rainforests, stylish eco-retreats and thrilling adventures. Sitting wi...

Known for its lush landscapes, rich produce and fresh seafood, there’s a reason the Sunshine Coast has been dubbed Queensland’...

Discover city sights and island delights on this three-day itinerary showcasing the many sides of a Brisbane getaway. Brisbane’...

A quintessential Tropical Queensland road trip awaits. Only 350 kilometres of road connects Cairns to Townsville and you can d...

Quench your thirst at these tropical watering holes. In a city as adventurous as Cairns, the key is to slow down and enjoy a re...

Add these Cairns tours to your travel itinerary. Don’t let all those laidback tropical vibes distract you from your travel goal...

Get to know some of the must-see coral reef sites on the Great Barrier Reef. Although the World Heritage-listed Great Barrier Ree...

From the World Heritage-listed Wet Tropics of Queensland to the scenic Atherton Tablelands, here are 15 Cairns waterfalls you need...

Taste your way around the city’s greatest cafes for coffee, brunch, and lunch. Searching for the best cafes in Cairns? Whether ...

Sharing the region’s incredibly diverse offerings, there’s a Cairns market out there to suit every taste, budget, and whim. ...

Wondering how to fill your time in Cairns? Tick off these must-do experiences. As the gateway to Queensland’s tropical north, C...

Looking for a bite to eat? From cheap eats to fine dining, make a booking at one of these top Cairns restaurants. Whether it's wa...

Soak up serious culture just 15 minutes from Noosa at the world-famous Eumundi Markets. Attracting over one million people each y...

Pair a soothing escape to the Sunshine Coast with a visit to a tranquil day spa in Noosa. Hoping for a little R&R on your nex...

Plan where to stay, splurge and dine along Hastings Street in Noosa with our foolproof guide. A collection of world-famous beac...

A trip to the Sunshine Coast isn’t complete without wandering through at least one or two local Noosa markets. From where’d...

It’s renowned for sophisticated dining and chic shopping but exploring Noosa with kids is a family holiday dream come true. Pic...

It’s time to ditch the crowds and discover the hidden gem of Queensland’s coastline. White sand beaches, nearby tropical isla...

Planning your next family holiday? Here’s how to play and have fun together. One of Australia’s most popular holiday destinat...

Bordered by Tallebudgera Creek, here’s how to spend a day in and around Palm Beach. Sitting on the Gold Coast’s southern bord...

Bubbles by the beach might squeal party times but nothing exudes Sunny Coast holiday vibes like a Noosa brewery or distillery. Al...

If you thought the best things to do in Noosa involved nothing more than a towel and your cozzies, think again. Slurp up that cof...

Flavour-packed produce and impeccable technique flow endlessly at the best restaurants in Noosa. Waterfront dining has long been ...

Lace up your boots and head out on an adventure, big or small, with these Gold Coast bush walks. The Gold Coast tends to conjure ...

Find an event that sparks excitement and save the date for your next visit to the Gold Coast. If you’ve been eyeing a trip to t...

If you can't get enough of witnessing nature's magnificent waterfalls, Byron Bay is within reach of some pretty memorable ones. T...

Discover a different side to Noosa on board the Great Beach Drive – one of Earth’s longest coastal paths. The charms of Noosa...

Quench your thirst at these coastal watering holes. Whether you’re looking for afternoon beers, a sunset spritz, pre-dinner win...

Taste your way around these casual coffee, brunch and lunch eateries. If you’re searching for the best cafes on the Gold Coast,...

This is your go-to guide to the best markets on the Gold Coast. Reflecting the eclectic spirit of the region, there’s a Gold Co...

Sit down with an ice-cold beer and enjoy. Consider yourself a beer lover? The Gold Coast’s brewery scene has exploded over the ...

Everything you need to know about the seven Gold Coast theme parks. Ready to get your heart racing? The Gold Coast is home to a h...

Wondering how to fill your time on the Gold Coast? Tick off these must-do ideas. With so much more to offer than just sparkly Sur...

Humpback highways have their place, but they’re no match for what has essentially become one big Airbnb between late May and No...

Consider this a reminder to always save room for a sweet treat. They say you can’t buy happiness, but you can buy dessert and t...

Top off your sun, sand, and surf break with a visit to one of these popular spas. Everyone needs a little TLC from time to time, ...

All that beach-going got you hungry? You’re in luck with these great eats. So much more than gorgeous coastline and nightlife, ...

Keep the whole family entertained in Brissy with these activities. Travelling with kids can be tough if you’re unsure what acti...

Whether you're eating in view of charming heritage architecture or serene water views of the Fitzroy river, here are the best rest...

Explore the historic heart of Central Queensland with a visit to one of the state's longest-standing cities. Rockhampton is one o...

Get those legs moving all while exploring more of Queensland’s natural beauty. Brisbane is full of incredible restaurants, a bu...

Whether you’re an art connoisseur or simply appreciate the beauty and talent that goes into it, the art scene is a thriving metr...

It isn’t a tropical escape until you dip your toes into the magical collection of Hamilton Island beaches, pools and secluded sw...

There’s plenty more things to do on this island paradise than sip on cocktails and catch magnificent sunsets. While lazing the ...

From Asian fusion and contemporary Italian to beachside fine dining and classic fish and chips, Hamilton Island restaurants whip u...

Dreamy scenery to take your breath away and lavish spoils crafted just for couples make a Hamilton Island honeymoon one you’ll c...

If you’re craving some good ol’ fashioned chicken schnitty and a schooner of ice-cold beer, we’ve got you sorted with these ...

Whether you’re after some fresh fruit and veg for your holiday home, a souvenir to remember your travels or a tasty bite from a ...

Bundaberg is brimming with things to do, whether you want to kick back at a distillery or pass through the Southern gateway to the...

Fish and chips on the beach, contemporary riverside dining or cocktails with an ocean outlook? It’s your call with these Townsvi...

Here are the eateries at the top of our list of places to enjoy breakfast in Townsville. From breaky favourites including smashed...

A lure for sea-changers, holidaymakers and backpackers alike, this picturesque town in Tropical North Queensland holds timeless ap...

Steeped in unspoilt natural beauty and boasting old-school holiday vibes with smart options for eating, staying and playing, and n...

A beach holiday in Mooloolaba on the Sunshine Coast truly has something to offer everyone, as former Queenslander Carla Grossetti ...

Put on your dancing shoes and check out Brisbane’s renowned live music scene. From the early days of The Saints and the Go-Betw...

Bundaberg is practically synonymous with alcohol. Don’t pass through without stopping for a drink! Bundaberg is the rum capita...

Linger a little longer in Bundaberg, with one of these accommodation options to suit your travel style. Dubbed ‘sugar country�...

Discover the second-largest sand island in the world. Endearingly referred to as ‘Straddie’ by the locals - and known as Minj...

Check out why the coast near Bundaberg has a reputation for some of the most beautiful beaches in Australia. Bundaberg has carved...

Grab a fork and discover what’s being served up in the ‘food bowl’ of Australia. Although it’s famous for its sugarcane, ...

Brisbane is blessed with a stunningly sunny climate, boasting some of the warmest year-round temperatures of any Australian capita...

Cool down at these highly recommended pools in Brisbane. With blue skies all year round, it’s always a good time to take a dip ...

Cape Tribulation is where the rainforest meets the reef, and for the ultimate guide on things to do here, you’re in the right pl...

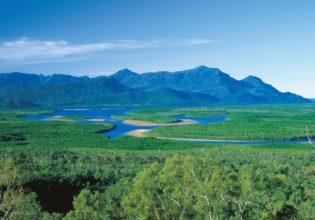

There’s no shortage of things to do in the Daintree and we’ve found the best. The Daintree Rainforest has a balance of relaxa...

It's time to sit back and let the experts show how to really experience their slice of paradise. Discovering remote swimming hole...

Prepare to be amazed by nature all over again. It might be one of Queensland’s most famous places to swim, but just how much do...

Get ready for a deep dive into the top K'gari (Fraser Island) lakes and swimming spots. As a country, Australia is in no way shor...

From visiting living museums to admiring vast orchid displays and idling away a day on a sweeping beach, these are the best things...

Ride an underwater scooter, meet the traditional owners of the reef, or sleep on a pontoon moored 39 nautical miles from land – ...

From the back of a jet ski, to the seat of a mountain bike or aboard a catamaran, there are countless ways to explore Airlie Beach...

What better way to see the delights of Hamilton Island than on one of its many walking trails, which include popular new routes th...

You’d be forgiven for thinking the Sunshine Coast is just one long stretch of sand, but if you reset your course inland there is...

A cruise in the dead of night offers up the perfect opportunity to witness the wonder of nature in all its kinky glory. We board ...

Snorkel the Great Barrier Reef, go deep into the Daintree and simply wind right down and relax in this charming tropical holiday d...

One of the seven wonders of the natural world, the Great Barrier Reef is a magnet for tourists and locals and for a few very good ...

Explore K'gari (Fraser Island) and you will not only discover the rainbow-coloured cliffs sacred to the local Indigenous people or...

Travelling Queensland’s tropical north during the wet season isn’t a deal-breaker and here’s why. As soon as you step off t...

The Outback is a mammoth proposition, so much so that it is sometimes hard to know where to start when it comes to exploring. Whe...

It’s hard to imagine that dairy cows and tanneries once dotted the landscape now home to cool cafes, coffee roasters and creativ...

Don’t let the pristine beaches and warm sunshine distract you. The Sunshine Coast is home to some of Australia’s best restaura...

Planning a trip to Queensland’s Sunshine Coast? Explore an abundance of beautiful beaches and discover their best-kept secrets. ...

There’s more to Hamilton Island than resort pools and swanky restaurants. For the ultimate family holiday, check out these top a...

Getting to the three-day music festival widely acknowledged to be the most remote in the world takes a bit of work, but is it wort...

Embark on the mother of all pub crawls to explore 45 of Australia’s best boozers. From remote country watering holes to pubs wi...

Bundaberg’s Mon Repos Beach is home to half the South Pacific’s nesting loggerhead turtles – and one of nature’s most anci...

Deep in the Queensland outback, David Levell discovers the stunning beauty of Cobbold Gorge, a chasm carved into the landscape tha...

Queensland has an abundance of gorges that are just as compelling as the stunning Cobbold. If breathtaking scenery is your thing, ...

The striking animal forms, chants and motions of the Laura Aboriginal Dance Festival are as relevant now as they have been for ten...

Novice sailor Celeste Mitchell discovers sailing Whitsundays on a catamaran without a captain is the best way to explore those fam...

A castle built out of love in tropical Queensland, Paronella Park is the fairytale you’ve never heard, writes Steve Madgwick. P...

It’s a slice of Queensland the way it used to be, in both a modern and ancient context, where two World Heritage areas just happ...

Celeste Mitchell skips the lengthy reservations queue and heads straight to the new bar within the grounds of hatted Sunshine Coas...

Perhaps the biggest road block, so to speak, to a Fraser Island driving holiday is fear of the unknown. Do I need to know how to ...

Caloundra used to be the Sunshine Coast’s quiet little sister. She’s no Noosa yet, but this southern (Sunshine Coast) belle is...

The Birdsville Races is an Australian outback bucket list item of mythical proportions, with around 7000 pilgrims covering thousan...

Alissa Jenkins comes face to fin with the most majestic of creatures in Hervey Bay, humpback whales, on one of Queensland's most m...

There are plenty of places to visit in Queensland starting with Queensland’s buzzing capital Brisbane a laid-back city meandering along the banks of the Brisbane River. There’s a whole, diverse state to explore, from South East Queensland to the Tropical North you’ll find the perfect base to explore.

One of the seven wonders of the natural world, the Great Barrier Reef is a magnet for travellers, ideal for romantic getaways or an adventure packed family holiday. Explore the Great Barrier Reef by snorkelling and scuba diving or view the magnificent reef from above with one of many operators offering tours of the world-heritage listed wonderland.

The Gold Coast has been synonymous with the quintessential Australian beach holiday for decades. The region attracts families, beach babes and surfers for it’s laid-back surf culture. In recent times, the Gold Coast has shed its kitschy stereotype to emerge as a cool and confident beach destination worth revisiting. Families flock to the Gold Coast theme parks while foodies are discovering the sophistication in the south at Burleigh.

One of Australia’s most precious natural wonders, the Daintree Rainforest, at 180 million years old, is the oldest continuously living rainforest in the world. When you visit this UNESCO World Heritage site, on the land of the Yalanji people, you’ll be inspired by the diversity of the flora and fauna and marvel at the distinct landscapes you encounter. Take a ‘dreamtime’ guided walk and learn fascinating stories about the Daintree or experience the Daintree from a different perspective by cruising, camping or ziplining through the rainforest.

Queensland’s natural beauty is utterly exploited during a go-with-the-flow journey from Brisbane to Cairns. Two cities stacked ...

Amid a sea of floating reefs, edible art and lush rainforest escapes, travellers to the Gold Coast today will find Queensland’s ...

From Queensland’s vibrant Great Barrier Reef to the colour-filled sunsets of Uluṟu, it’s time to take another, deeper look a...

It’s time to change up your algorithm and disconnect from the daily grind with a holiday at Lizard Island Resort, the ultimate l...

Looking for a holiday with everything from world-class museums and galleries to pristine beaches and nearby waterfalls? Welcome to...

Get to know one of Queensland’s most adventurous cities. A place of natural beauty, Tropical North Queensland has plenty of pl...

Is this long-weekend cruise from Brisbane the holiday to tick all boxes? Tiana Templeman boards Quantum of the Seas to find out. ...

Go beyond cafe culture to connect with the natural wonders of Noosa National Park. Noosa is not just a private playground for th...

Uncover where to eat, play and stay in this bustling Gold Coast beach town. Sorry to burst your bubble if you’ve only just disc...

Discover part of the most extensive subtropical rainforest in the world. Part of the Gondwana Rainforests of Australia World Her...

Get to know a new side of Broadbeach and plan your long weekend. Forget everything you think you know about the Gold Coast becaus...

Surf, swim or sunbake on these gorgeous sweeps of Gold Coast sand. Queensland isn’t short on beaches, but it’s fair to say th...

Just steps beyond the sun and surf lie a huddle of personality-packed Gold Coast suburbs, each humming with its own distinct brand...

The kids will sleep like a log at these family-friendly stays. Finding the ideal spot to rest your head after a big day of explor...

Although the seductively laid-back islands scattered in the sparkling waters between Cape York and Papua New Guinea lie well off...

Need a better reason to visit the southernmost destination on the Great Barrier Reef? We didn’t think so. The Bundaberg Region ...

Whether you want water views, panoramic vistas, adrenaline-fuelled adventures or lazy days on relaxed islands, Brisbane is packed ...

From scenic flights to yacht charters to total immersion in the Great Barrier Reef, here’s how to make the most of your day trip...

Visit an underwater museum, take a ferry to a tropical island, chase waterfalls through the rainforest and wander street-art-fille...

Much more than just a gateway to paradise, Airlie Beach is a worthy place to linger, says long-time visitor Craig Tansley. Find ou...

Located on a long reach of the Thomson River, this colourful town is in the heart of the Australian outback. It also came in at no...

From huge flower festivals to quirky little rail museums and the city’s nascent arts scene, there’s plenty of things to do in ...

The so-called Garden City is brimful of cafes – take your pick from eight of Toowoomba’s best. The pretty little city of Toow...

From fine dining ventures to rustic coffee shacks by the beach, here are seven of the best Hervey Bay restaurants, bars and cafes....

Dust off the sand and prepare to frolic through the rolling hills of the Sunshine Coast Hinterland. Escaping the suntanned crowds...

Port Douglas is home to a large population of crocodiles. Here are five top places to spot them. Not all of the residents in Trop...

Stunning Port Douglas beaches and swimming spots to cool off at year-round. One of the most popular things to do in Tropical Nort...

Are you trying to decide which of the Great Barrier Reef islands are right for you? We break down what six of the best have to off...

Play castaway on one of these unmissable islands to visit off the coast of Cairns. Take a patch of white sand, add a few palm tre...

It’s pretty easy to find your happy place when holidaying on Hamilton Island. And, with a bit of insider knowledge, and forward...

Hervey Bay is so much more than a simple stopover en route to Fraser Island, as we discover on a bliss-filled few days on the Fras...

While most people pass through this part of Queensland on the way to somewhere else, the outback region of Balonne Shire has plent...

Travel from the coast to the outback and back again on any number of road trip journeys through Queensland. From stunning rainfore...

Kara Rosenlund captures the essence of a summer in Queensland on North Stradbroke Island. Summer in Queensland means big blue ski...

From camelcinos to Eweghurt, discover the dairy delights of the scenic rim, and plenty more surprises besides. Known as the 'gree...

A destination in its own right, discover a different side of the Great Barrier Reef gateway. Dusk is a deafening time of day in N...

Take a road trip through Queensland’s Granite Belt to discover some of the country’s most dramatic scenery and best cool-clima...

It’s the dream of every parent: the perfect family holiday, where tears and complaints are left at home, replaced by smiles and ...

It’s known as the gateway to the Great Barrier Reef, but the heart of Tropical North Queensland also has plenty of urban attribu...

Spend a weekend discovering QLD's newest foodie haven, sourced from delectable local produce, before taking in the surrounding nat...

With 74 islands to choose from in the Whitsundays, our guide tells you which one is the best fit for you to stay. Grab some well-d...

With some of the planet’s best scuba diving spots, the Great Barrier Reef is a natural playground in our own backyard waiting to...

If you're looking for a beautiful, tranquil setting for rest and relaxation, look no further than beautiful Lizard Island. Where ...

Leaving city life far behind isn’t hard when Brisbane’s Moreton Island is involved. It’s easy to overlook the simple beauty...

Rainbow Beach isn’t the kind of place that you stumble upon by accident, which is a massive bonus. The weeny seaside village not...

The drive between Boulia and Winton in Queensland's West covers some of the most spectacular land in our country, but few are luck...

Hayman Island will always bring to mind images of seaside opulence, but there's more than just white sand and water. Words by Geor...

It was business as usual for travel journalist Craig Tansley, when an invitation to Magnetic Island arrived in his inbox. Next thi...

Ever daydreamed about the world's largest sand island, K'gari (Fraser Island)? Wondered what lies across the 166,000 hectares of l...

You’ll find options in Queensland to suit every budget from camping and caravan parks, budget hotels to beachside resorts, boutique hotels and luxury accommodation.

Wondering where to stay in Queensland? Whether you’re planning a family holiday, city break, adventure holiday, romantic getaway or luxury experience there is a destination to suit your style from a coastal holiday on the Sunshine Coast, to a road trip in the Outback, Queensland has the perfect accommodation to suit your style and budget.

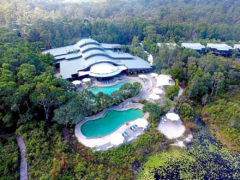

Queensland is a popular choice for a honeymoon or romantic getaway and luxury lodges are the perfect choice to retreat from the world. Spicers Peak Lodge is the highest non-alpine resort in Australia with valley views, fireplaces and a hatted restaurant making it a dining destination worth the detour to the Scenic Rim. In the tropical north, Silky Oaks Lodge is the ultimate luxury eco lodge in an unrivalled location on the tranquil Mossman River just downstream from Mossman Gorge.

Looking for luxury hotels in Queensland? Look no further than qualia the darling of Australian luxury on the pristine Hamilton Island. In Brisbane, The Calile Hotel has brought sophisticated style and laid-back elegance to the river city. Meanwhile, The Star Gold Coast brings the glitz and opulence to the Gold Coast, surrounded by bars, restaurants and entertainment precincts alongside the thrills of a world-class casino.

Tropical North Queensland presents like a large-scale triptych with sequential stays at three key Luxury Lodges of Australia prope...

It’s time to take another look at the luxury offerings in the gateway to The Whitsundays, Airlie Beach. The Whitsundays are one...

The Sheraton Grand Mirage Resort Port Douglas might be one of the country’s most iconic beachfront resorts, but it’s also one ...

Your go-to list on where to spend your next luxury escape in Cairns. Whether you’re looking for luxury of the five-star variety...

Accommodation in Cairns is as diverse as its landscape, so you can afford to be choosy on your next sojourn to Tropical North Quee...

Settle into one of these stylish Airbnbs on your next tropical escape. With so much beauty to explore in Cairns and beyond, stayi...

Your go-to guide on where to find Palm Cove accommodation to suit every budget. For that instant ‘on holiday’ feeling, look n...

Not all holiday rentals are created equal which is why we’ve uncovered the full range of stand-out Airbnbs in Noosa for your eas...

Turn your escape into an unforgettable adventure at the best Noosa caravan parks, camping and glamping spots. From sites aimed at...

Exploring the chic coastal pearl of the Sunshine Coast requires an epic slice of Noosa accommodation from which to launch off. St...

Need a break from the city? Discover what to do and where to stay in this natural wonderland. Less than an hour’s drive from th...

A little slice of rock and roll heaven just steps away from the sand and surf, The Pink Hotel in Coolangatta is a true original. ...

Jaw-dropping scenery and rainforest adventures are calling from the finest Mt Tamborine accommodation picks. Foggy mountaintops a...

Score instant access to the Gold Coast’s trendiest bar and dining scene with one of the best Burleigh Heads accommodations. Hip...

Declutter a tangle of towers with our cheat sheet to the best Surfers Paradise accommodation. Dwarfed by rows of countless high-r...

Make it a (mostly) tantrum-free holiday they’ll remember forever with the best family accommodation on the Gold Coast. Laid-bac...

Unpack and unwind close – but not too close – to central Gold Coast action with the dreamiest Broadbeach accommodation. Surfe...

Switch out endless activity for much-needed downtime with Coolangatta accommodation on the easy, breezy southern Gold Coast. As m...

Keep the fam bam up to their eyeballs in outdoor activity by escaping to the best caravan parks on the Gold Coast. Trips to Disne...

The Irwin family’s passion for conservation extends into Australia Zoo’s deluxe eco-lodge, which offers the ultimate wildlife ...

Create sun-soaked memories without stepping foot outside your holiday digs thanks to some of the best Gold Coast resorts. Epic ex...

Turn off and tune into your body with a stay at a game-changing health retreat on the Gold Coast. A steady wave of outdoor activi...

Reconnect with nature in spectacular fashion through the best glamping on the Gold Coast. High-rise hotels and sizable resorts mi...

From ritzy hotels with private marinas to low-rise beachfront resorts with swim-up bars and multi-bedroom villas, there’s no sho...

With an average of 300 sunny days a year, there really is no better way to experience the beauty of the Gold Coast than by sleepin...

Ditch hotels filled with unfamiliar faces and whirls of activity in favour of a wildly cosy Airbnb on the Gold Coast. When the ca...

Big, bold and brash, the W Brisbane brings unmatched vibes to the sunshine state. When the W Hotel in Brisbane opened its doors, ...

There’s no such thing as run-of-the-mill when it comes to luxury accommodation options in Brisbane. From enhancing a summer hol...

Discover the heritage heart of Central Queensland with a stay in sunny Rockhampton Rockhampton is a regional city bursting with h...

Cool hideouts, beach-front hotels, five-star resorts and grand holiday homes shine bright amongst the stellar selection of Hamilto...

Lagoon-style pools and dining extravaganzas extend to visitors of all ages thanks to the wonderful assortment of Hamilton Island f...

Famed for its stretches of crystal-clear coast, award-winning distilleries and abundant produce, Bundaberg serves as an excellent ...

From bright and breezy beachfront motels to tropical resorts with poolside bars to luxury island hideaways, Townsville has a tonne...

Check out these 10 short-term rentals in Brisbane with a unique twist. While an influx of new and innovative hotels has overtaken...

With its trio of sustainable hotels and plethora of wining and dining options, Crystalbrook Collection is helping revitalise this ...

Brisbane’s first urban resort feels like a glamorous trip to Palm Springs. Take a peek at Australia’s first urban resort. Cel...

From quirky cabins to luxury escapes, here are some of the best places to stay in the Sunshine Coast Hinterland. From a luxurious...

Sleeping under the stars in the Daintree is an experience you will never forget. Cape Tribulation is the only place on Earth wher...

Do you want to stay at the only place in the world where two UNESCO World Heritage sites collide? Well, you’re in luck… Cape ...

Wake up to nature at your window with these incredible stays. The Daintree Rainforest is part of the UNESCO World Heritage-listed...

From lake island getaways to beachfront sites, and leafy yet central amenity-laden parks, meet your match with these Hervey Bay ca...

From modern resorts to beachside glamping and spacious holiday parks, take your pick from these seven Hervey Bay accommodation opt...

Whether you’re in town for business or pleasure, these seven Toowoomba hotels, caravan parks and holiday homes deliver the goods...

From elegant glamping to family friendly holiday parks, here’s where to camp or glamp on the Sunshine Coast. Being in the great...

From swanky resorts with world-class golf courses to family-friendly holiday parks, here’s our guide to the best Port Douglas ac...

Airlie Beach accommodation for every budget: from swish hotels and resorts to well-kept family-friendly camping grounds and carava...

Quick break in Queensland? Drop anchor in Airlie Beach, find luxury in the outback and nightfall in a national park. Freedom Sho...

Not only will these offerings impress your pets, but they’re also extremely people pleasing too. Queensland’s Sunshine Coast ...

Let these dreamy island accommodation options tempt you into a stay on K'gari (Fraser Island). The local Butchulla tribe refer to...

Discover why UNESCO defined K'gari (Fraser Island) as a place of exceptional natural beauty. K'gari (Fraser Island) is home to ex...

There are a plethora of ways to experience the Great Barrier Reef, but for a completely unique experience don't pass up the chance...

If you’d like to get as close to the Great Barrier Reef as possible, you’re going to need somewhere to stay. Right? Listing a...

Let your appreciation of good design guide you to Burleigh Heads for a very stylish stay. There is a small coastal town in northe...

An idyllic island bounces back to be better than ever with the resurrection of an Australian icon. When visiting an icon, opportu...

Indulge in the majesty of Mother Nature Unspoilt coastline overlooks the kind of turquoise blue that instantly invites serenity o...

It's the first 100 per cent solar-powered resort on the Great Barrier Reef and the newest to be built in the Whitsundays for years...

Finding your own slice of paradise on the Sunshine Coast is not an easy feat. With so many areas and accommodation options to cho...

In 2012 an elegant simplicity and a fine attention to detail turned a corner of Hamilton Island into the best resort in the world....

What if Queensland’s Sunshine Coast offered more than a summery beachside retreat? Words by Celeste Mitchell, Photography by Kri...

These Queensland family resorts keep kids entertained and adults sane; it's play time for the children and spa time for the adults...

HINCHINBROOK WILDERNESS LODGE is currently closed as it has been destroyed by cyclones and fire. We hope it will be reborn soon. ...

There are plenty of tours and packages to make the most of your Queensland holiday. Choose from our ultimate Queensland bucket list including a visit to the award-winning Bundaberg Rum Distillery for a unique Blend Your Own Rum Experience.

The Daintree Rainforest is a world away from civilisation but a snap to get to. And the drive north from Cairns is something worth...

Clear the coastline and your conscience during a Zero Co Untrashed Eco Tour on K’gari (Fraser Island), just like Carla Grossetti...

Want to see a salty in the wild? There’s no better place than a Daintree River Cruise. As Queensland's crocodile country, Dain...

To help you plan ahead, we’ve rounded up 10 of the best tours to book in Port Douglas. With its vast tracts of rainforest and r...

Whether you’re up for snorkelling, diving or perhaps witnessing a mass coral spawning event, these Far North Queensland tours of...

The Great Barrier Reef is a living structure under pressure, threatened by climate change, pollution and land run off, and other f...

Travel used to be simple: photographs in front of famous monuments or tasting the local cuisine. Now we need to be the fastest, wa...

The only way to experience the rugged landscape of Queensland. Mountain biking is a little misunderstood. It conjures images of R...

You read that right: catching bulls in Cape York... Michele Maddison takes us along on the ride of her life. Tranquillity. As y...

© Australian Traveller Media 2024. All rights reserved.