30 October 2023

![]() 8 mins Read

8 mins Read

Sixty kilometres off the edge of Western Australia, an island smaller than a footy oval is the last place you’d expect to find a thoroughly decent espresso. But at 3pm each day, Pete Scarpuzza heats up a shiny pot on the stovetop and waits for friends to come. Like clockwork, locals wander to the weathered cottage for a chinwag, exchanging smiles and stories for a fresh cup of caffeine.

Only seven people reside on Basile Island, and that’s when it’s busy. Usually, there are only three. The woolly cray fisherman and his brother Nino are carrying on a tradition set by their father, one of the first fishermen to colonise this remote archipelago of 122 islands, named the Houtman Abrolhos.

An Australian sea lion rests offshore from the islands. (Image: Fleur Bainger)

Few people even know these specks exist in the ocean, off the state’s mid-point. As rare visitors, we’re welcomed with an elbow to the ribs, and told our invitation here is one way of freshening up conversation among the island regulars.

We’re on a five-day exploratory cruise and, as espresso cups are handed around, we hear that Eco Abrolhos’ 32-person catamaran is the only tourism vessel permitted to stop at Basile. It’s partly to do with the chocolate cake our hosts bring along, but mainly it’s about the connections made over the 30 years they, too, fished these waters. “We took it for granted, and eventually we looked at it and thought, ‘It is pretty special’,” says Eco Abrolhos’ owner Jay Cox, a big bear of a man with the booming voice of a market auctioneer. Jay and his wife Sonia raised two kids on the islands; son Bronson is our skipper. “It’s just pristine. It’s the remoteness, the wildlife,” says Cox senior. “It grabs you.”

Tammar wallabies are native to two of the islands. (Image: Paul Hogger)

This is a special time for the islands, since 2019 marked 400 years since a Dutch merchant sailor came across the flat crusts of land en route to the Spice Islands of Indonesia. Captain Houtman spotted the archipelago 151 years before Captain James Cook arrived on the east coast of Australia.

Abrolhos is believed to be a Portuguese term meaning ‘spiked obstructions’ – a fortuitous descriptor of these harsh, coral-rimmed islands that barely peek above the waterline. Numerous ships subsequently ran aground, including the one named Batavia, whence the aftermath of treachery and murder still produces goosebumps – and skeletons. But more on that later. For now, we’re blissed out on the Swiss Family Robinson-style existence of the past eight decades.

We tramp down a raw-wood jetty and take in Basile’s row of boxy, fibro shacks decorated with shells, buoys and frayed rope. Nicknamed Little Italy, this stretch is painted at first sympathetically, in turquoise, cobalt and emerald, before things get louder with red, violet and fluorescent green. “When the wives and kids began living on the islands, the colours followed,” says Pete, who is among the last of the 150 fishermen who once called the islands home.

Until a decade ago, abodes linked by white, coral paths led to community clubs, tiny schools and over-sea drop toilets that fanned around the landforms like fingers on a hand. Twenty-two of the islands bustled with close-knit, communal life. “We had power generators in the early days, rainwater tanks, bucket showers and kerosene fridges,” recalls Jay. “You had to write letters; there was no phone or internet. When I first started going out with Sonia, I’d have to wait five days for the carrier boat to come out with the mail. You say things in letters that no one else sees.”

Back then, the islands would buzz from March to July; now, a quota-style measuring system of the cray catch means it’s not worth leaving the mainland for long spells. Instead, most keep to the mainland around Geraldton and fish to market demand.

Crayfish fishing camps are dotted throughout WA’s Abrolhos Islands.

Jay may have farewelled his commercial fishing days, but his passion for seafood remains strong. Each morning, pots are pulled, and mealtimes are a showreel of the ocean’s bounty: decadent crayfish pizza, creamy seafood chowder, surf and turf, and even chunky crayfish dip.

When we snorkel over coral gardens in the glass-blue water and spot wafting rock-lobster feelers, it’s hard not to think of how they might be repurposed. The marooned crew of the Batavia probably had similar thoughts. By night in 1629, the pride of the Dutch fleet hit reef, stranding more than 250 survivors on the islands. With little fresh water, barely any food and no natural shelter, the ship’s commander left to seek help. While he rowed to Indonesia, a gang of mutineers slaughtered some 126 men, women and children – Australia’s first mass murder. Their aim was to keep the scarce resources, and the heavily laden ship’s loot, for themselves.

When we set foot on the Island of Angry Ghosts, its pristine inlet of white sand, crystalline water and a playful sea lion seems an incongruous match for the horrors meted out here. But as we walk along coral rubble that tinkles like glass, the sun beats down and thoughts wander to those people, stuck in a place that’s as barren and bitterly inhospitable as it is beguiling.

We pass low shrubs that claw at our legs and stop at a stone jail where the ringleader, Jeronimus Cornelisz, was held before being tortured and hung as punishment for his staggering crimes. He ordered the killing of more than a third of those shipwrecked; their skeletons continue to be unearthed, most recently by archaeologists in 2017.

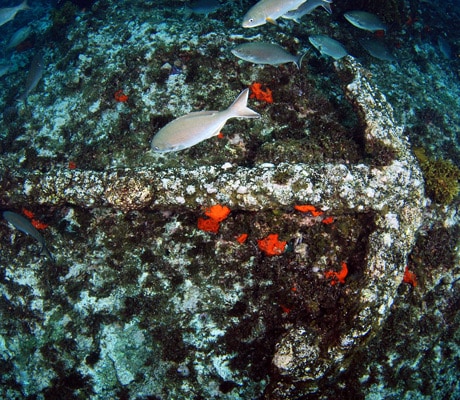

An anchor from the Batavia Shipwrekc on Abrolhos. (Image: Paul Hogger)

The Batavia shipwreck was officially discovered in 1963, but gnarly Abrolhos fishermen claim they found it earlier. The reef can’t be snorkelled during a fierce swell, but we strike a calm day and splash in. I barely notice the colourful schools of parrotfish as enormous anchors loom into view, scattered on the sea floor like pick-up sticks. I count seven, their hefty curves covered in coral. I kick my flippers towards the submerged vessel. There’s nothing left of the vessel but a scar in the ocean floor, cutting through the coral in the shape of a ship’s bow. It’s eerie the sea has never reclaimed the impact zone.

Nearby Big Pigeon Island is home to one of the last remaining community clubs, where beers start at $5 and dinner is advertised on the whiteboard: $8. There are fewer than a handful of punters inside. One of them, known simply as Spags, claims he was the first to swim over the Batavia wreck, when he was 15 years old. “I found rosary beads, a silver pot, all sorts of things. I gave most of it to the museum,” he says.

There is a strong sense of community on the Houtman Abrolhos Islands. (Image: Fleur Bainger)

A silver coin hangs around his wrinkled neck. When I point it out, he says it’s the only piece of salvage he kept. The markings are German, with a picture of Roman King Ferdinand on it, forming evidence the Dutch ship traded with many ports on its global journey before it ended here.

As we dinghy back to our mothership, the molten copper hues of sunset reflect in the ocean, engulfing sky and sea. As darkness takes hold, we see a dozen sharks floating in the blue space at the back of the boat. Like everything in the Abrolhos, the scene is brutal and beautiful in one.

The five-day Eco Abrolhos cruise departs from Geraldton, a 4.5-hour drive north of Perth, or an hour’s flight with Qantas. Abrolhos cruises run February to May and September to October.

Eco Abrolhos catamaran. (Image: Paul Hogger)

The Gerald is an impressively chic boutique hotel in Geraldton’s heart. The town’s main shopping street, beach and esplanade are less than a minute’s walk away.

The Gerald’s nautically themed rooftop bar, called The Old Man And The Sea, dishes up tasty, wallet-friendly share dishes – go for the fish tacos.

Stop in at the free-entry Museum of Geraldton for an encompassing history of the Batavia and other shipwrecks along the coast.

For more information visit australiascoralcoast.com

I am one of 10 members of The Marmion Angling and Aquatic Club Dive section that is going to the Abrolhos islands next week on Seaestar boat charters for a week of diving, underwater photography and fishing. This is my second visit to this local gem of islands. The underwater environment is simply beautiful.

MOST INTERESTING INDEED